Category Archives: PgCert Practical Science Communication

MSc projects: science communication research in the real world

Clare Wilkinson

During our MSc Science Communication at UWE Bristol we focus a lot of effort on supporting students to develop their networking and employability skills whilst they study our modules. That’s one of the reasons why our graduates seem to be pretty successful in finding a job in science communication after studying with us and it also means our students get to meet a wide range of science communication practitioners and academics who are working at the ‘coalface’.

One way in which we build in an opportunity to work with an external organisation is via our Science Communication project module. Since the programme started 15 years ago we’ve had well over 150 students working on projects with our Unit and in 2009 we introduced a specific opportunity for students to conduct their projects in partnership with an external organisation. This has resulted in collaborative projects with organisations and charities including We The Curious, the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, Public Health England, and the British Science Association to name just a few. As our current students complete their projects we spoke to some of the students working with external organisations this year about their experiences.

Anastasia Voronkova

Anastasia Voronkova, joined our programme from her home in Russia in September 2016. Anastasia said ‘in my project, I am analysing Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust’s, one of the biggest international charities’, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram social media strategies and trying to understand how the audiences on these websites perceive conservation related posts.’ Digital and social media communication have been popular topics for our project students in recent years, and it’s also a space where many organisations are still finding their way, or coming up with contemporary and new approaches to reach audiences.

Anastasia was pleased to have chosen to work with an external organisation, who had been offering ‘great help and support’ alongside her UWE supervisor. Anastasia said her project had also ‘given me a unique opportunity to gain some knowledge about conservation from its active practitioners and to contribute to that field, even if only in the form of a research.’

Lindsey with some of her participants

Lindsey Cooper is a part-time student who began studying her MSc in September 2014 whilst working as an outreach and recruitment officer at Plymouth University. Lindsey has been working with We The Curious (formerly At-Bristol) on her MSc project, which offered exciting opportunities to explore not only the combination of art and science but also the relationship of science centres to underserved audiences, in her case those with physical disabilities. Lindsey said: ‘I have been evaluating a new exhibit called The Box, to see if people with physical disabilities interact and respond to the exhibit in the same way as individuals without a disability.’ The Box celebrates the synergy between art and science, and feature exhibitions and artists that occupy the space where art and science meet.

‘I have really enjoyed the experience of working with an external organisation on my project’, said Lindsey, ‘but involving more individuals has (inevitably) made the process more lengthy and complex. It took me a while to develop my research question and balance what I was interested in with what was useful to the exhibit designers at We The Curious. However, I feel like I’ve ended up with a stronger research question and results than I would have otherwise.’

Ben Sykes on site at Steart Marshes

Ben Sykes was also working whilst undertaking his MSc, though in his case this involved him developing his freelance writing career, following a change of direction after many years working at Research Councils. Ben worked with the WWT Steart Marshes which is a created wetland in Somerset. Ben said ‘this is one of the largest and most ambitious managed coastal realignment projects ever undertaken in the UK’ and the project provided him with a real opportunity to get on site at with the WWT, and to consider the issues they face in ‘communicating the science behind its creation and the ongoing research being conducted there by a consortium of universities.’

Ben described his project as a ‘huge challenge’ communicating in an outdoor, remote environment but by creating three Quick Response (QR) codes which were deployed across the reserve, Ben was able to see some real impacts from his work. Ben continued ‘By linking this to web-based science content, my project resulted in a third of Steart Visitors accessing content on the web and learning something about science. It was a super project to work on.’

Our thanks to all organisations who contribute their time and ideas to work with our students, as well as Ben, Lindsey and Anastasia for their contributions to this blog post. If you are based at an organisation who would like to work with student projects in future please contact Clare.Wilkinson@uwe.ac.uk. Find out more about our Science Communication programmes.

Welcoming Hannah Little, new lecturer in the Science Communication Unit

My name is Hannah Little. I’m a new lecturer at the Science Communication Unit. I will be teaching Science Communication at foundation, undergraduate and postgraduate levels, specially focussing on areas in digital communication.

Previously, I have worked professionally in science communication, primarily coordinating the STEM Ambassador and Nuffield Research Placement programmes in the North East of England. I have come to the Science Communication Unit after completing a PhD at the Artificial Intelligence Lab at the VUB in Belgium, and a PostDoc at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics. My work throughout both my PhD and PostDoc was primarily on the evolution of linguistic structure. One method I have used in my research is cultural transmission experiments in the lab.

These experiments investigate how language (or any behaviour) is changed as a result of being passed from one mind to another in a process similar to the game “Telephone”. One person’s output becomes the input for a new person, whose output is fed to a new person and so on! This method is being used more and more to look at processes of cultural evolution, and I am interested in using these methods to investigate processes in science communication.

Norman Rockwell (1894-1978), “The Gossips,” 1948. Painting for “The Saturday Evening Post” cover, March 6, 1948.

I see existing work in cultural evolution fitting into science communication in 3 main areas:

Science Writing

Using experiments to investigate how stories and information are culturally transmitted isn’t new. As far back as 1932, Bartlett’s book “Remembering” describes experiments that looked at how transmission of a memory from one person to another can affect what information persists, and what is forgotten through a failure in the transmission process. More recently, Mesoudi et al. (2006) used similar experiments to systematically investigate whether information is transmitted more faithfully when it is embedded in a narrative around social interactions compared to equivalent non-social information. I am keen to explore these findings in practical contexts in science communication, for instance looking at how well information persists from scientific article to press release to media story as a result of different types of content in a press release.

Digital Communication

The internet is the home of the “meme” a culturally transmitted idea (this could be any idea, picture, video, gif or hashtag). New methods from big data analysis are being used by scholars interested in cultural evolution to explore the proliferation of memes, and this is even starting to happen in science communication too. Veltri & Atanasova (2015) used a database of over 60,000 tweets to investigate the main sources of information about climate change that were proliferated on twitter and the content of tweets that were most likely to be retweeted. They found that tweets and text with emotional content was shared more often. These findings fit with the findings from Mesoudi et al. (2006) above, demonstrating that multiple sources and methods can be used to accumulate evidence on what it is that allows scientific information to be a) transmitted in the first place, and b) transmitted faithfully.

Hands-on science activities

Another hot topic in cultural transmission is the role of innovation and creativity in the transmission of information resulting in an accumulation of information. Caldwell and Millen (2008) investigated this process using an experiment whereby participants were asked to build the tallest tower possible using just dried spaghetti and blue tack, or the paper aeroplane that flew the furthest. Participants were able to see the attempts of people who had gone before, giving them the option to copy a design that had already been tried, or innovate a new design. The study found that participants got better at building successful towers and aeroplanes later in transmission chains than earlier, indicating that successful engineering skills were being acquired just from the process of cultural transmission. This, of course, is a brilliant finding in its own right, but there is a huge amount of scope for using this paradigm to investigate what affects cumulative cultural evolution in the context of issues relevant to science communication. For example, does explicit learning or simple imitation affect rates of innovation and success? This question has previously been explored using cooking skills in Bietti et al. (2017) and paper aeroplanes in Caldwell & Millen (2009). You can also use these methods to investigate questions about whether the characteristics of the person transmitting the information plays a role in faithful transmission or innovation (e.g. their gender, age, perceived authority, etc.).

Together, I think these case studies of existing literature outline the scope of methods and insight available from the field of cultural evolution to questions in science communication, and I look forward to working with the unit at UWE to generate some new research in these areas!

Hannah Little

References

Bartlett, F. C. (1932). Remembering. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Caldwell, C. A., & Millen, A. E. (2008). Experimental models for testing hypotheses about cumulative cultural evolution. Evolution and Human Behavior, 29(3), 165-171.

Veltri, G. A., & Atanasova, D. (2015). Climate change on Twitter: Content, media ecology and information sharing behaviour. Public Understanding of Science, 0963662515613702.

Never say never again…

After my PhD viva in 2004, I promised myself I’d never again study for a qualification. Having gone straight from A-levels through a degree to a doctorate, I felt as if I just couldn’t learn anything more. But a decade later, I found myself at a career crossroads trying to figure out what to do at the end of my maternity leave.

Inspired by my elder daughter’s curiosity, I set up a blog, Simple Scimum, to answer questions about science and nature. Slowly, as the blog gathered followers, my confidence grew; and when one of my daughter’s friends asked if I would answer her science questions too, I knew I had to turn science writing into something more than a hobby.

I began searching for jobs that involved writing about science and quickly realised that a qualification in science communication would be an advantage. So, I googled ‘sci comm Bristol’ and found UWE’s MSc in Science Communication, which sounded brilliant but was more than I could manage whilst working part-time and looking after two young children. However, the Postgraduate Certificate in Practical Science Communication was exactly what I was looking for: a one-year, part-time course with intensive teaching blocks, offering hands-on experience and links to industry. I applied for the September 2016 intake and won a bursary towards my tuition fees: I was going back to university!

I felt nervous about returning to study after such a long break but I knew that this was just the first step along a new career path.

The ‘Writing Science’ module was an obvious choice, with the opportunity to create a magazine and develop a portfolio just too good to miss. I learned the essential elements of journalistic practice and wrote a bylined article for UWE’s Science Matters magazine. But the real highlight was a three-hour workshop on ‘how to write a book’ – I’d love to write science storybooks for children, and came away bursting with ideas, enthusiasm and an action-plan to turn my dream into reality. (Roll on NaNoWriMo…!)

But it was through the ‘Science in Public Spaces’ module that I discovered just how strongly I want to inspire young children and engage them with research. I designed ‘Simon’s Box’ to talk about genetic disease and genome editing with GCSE pupils in local schools. And I had the best time in the Explorer Dome learning about science shows for young audiences. Seeing how to encourage children to learn through stories and play was a fantastic experience and a seminal moment in my desire to become a science communicator.

At times I found it hard to juggle study, work and childcare but the intensive teaching blocks made it easier for me to attend lectures and workshops. I paid for my younger daughter to go to nursery for an extra morning each week and used that time for reading and research. Still, I often found myself studying between 8pm and 10pm, when the kids were tucked up in bed, and I was grateful for 24-hour online access to UWE’s library facilities. But now the hard work is over and I’m just waiting for my final results.

Over the past year, I’ve been part of a supportive cohort of students who are committed to science communication. I’ve developed the confidence to pursue a new career path and given up my old job to become a Research Fellow in UWE’s Science Communication Unit. Before the PGCert, I dreamed of working in science communication but now I’m actually doing it.

Kate Turton

Thinking inside the Box(ED)

Watching scientists pitching their research projects felt like being in an episode of Dragons’ Den. I sat among a group of fledgling science communicators, tasked with choosing a project to develop into a school science activity. My first assignment as a new student, freshly enrolled on the UWE PGCert in Science Communication, was to create an activity suitable for UWE’s BoxED scheme!

I was paired with Gabrielle Wheway, who studies DNA to understand how mutations in genes alter their function and was awarded a prize for her research on retinitis pigmentosa, an inherited form of blindness. We met over coffee to discuss how I could design a hands-on activity that would communicate an aspect of Gabrielle’s research1 to a secondary school audience within a 45-60 minute session in a classroom environment.

I was paired with Gabrielle Wheway, who studies DNA to understand how mutations in genes alter their function and was awarded a prize for her research on retinitis pigmentosa, an inherited form of blindness. We met over coffee to discuss how I could design a hands-on activity that would communicate an aspect of Gabrielle’s research1 to a secondary school audience within a 45-60 minute session in a classroom environment.

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is caused by mutations in the genes that control vision. Most people with RP are born sighted but experience gradual, progressive deterioration of vision as they grow older. Symptoms can begin at any age and there is no way to predict how quickly the condition will progress. Early signs include difficulty seeing at night and tunnel vision, followed by loss of colour and central vision. Gabrielle mentioned the charity RP Fighting Blindness and I contacted their local support group to learn more about the disease and what it is like for people living with RP.

Early signs include difficulty seeing at night and tunnel vision, followed by loss of colour and central vision. Gabrielle mentioned the charity RP Fighting Blindness and I contacted their local support group to learn more about the disease and what it is like for people living with RP.

Over the next few weeks, I started to formulate an idea: my Box would draw on lived experiences of RP and build on four themes in the National Curriculum for Biology at Key Stage 4 (i.e. non-communicable diseases; gene inheritance; impact of genomics on medicine; and uses of modern biotechnology and associated ethical considerations). It would be targeted towards students in Year 10, who could bring in broader perspectives from other GCSE subjects, such as ethics, religious studies or philosophy.

The people from RP Fighting Blindness had shown me some glasses that simulate a type of visual deterioration common in RP. I decided that my a ctivity would involve experiencing what it feels like to have an altered field of vision. I also wanted to establish a personal connection, and found a short film about being diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa. Finally, I thought about genes as units of inheritance and how they are passed from one generation to the next. Under the working title “Simon’s Box”, my activity looks at genetics and inherited disease using RP as a case study.

ctivity would involve experiencing what it feels like to have an altered field of vision. I also wanted to establish a personal connection, and found a short film about being diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa. Finally, I thought about genes as units of inheritance and how they are passed from one generation to the next. Under the working title “Simon’s Box”, my activity looks at genetics and inherited disease using RP as a case study.

Designing a BoxED activity has been an enjoyable experience. I’ve learnt about the National Curriculum for science, researched good practice in designing exhibitions at Science Museums, and delved into learning styles and education theory. I’ve rediscovered a personal interest in genetics and human biology, and developed something of an affection for RP. And I’m delighted that we are now getting ready to roll it out to local schools and festivals. So, if you’re planning to attend the Festival of Nature or Cheltenham Science Festival in June, come along to the UWE BoxED stand and try out some of our hands-on science activities!

Kate Turton

1Gabrielle’s research is funded by Wellcome Trust and National Eye Research Centre

New and notable – further selected publications from the Science Communication Unit

Last week we posted details of our work on environmental policy publications as well as our research on outreach and informal learning. This week’s blog highlights our work in public engagement with robotics and robot ethics, as well as our work on science communication in wider cultural areas, including film, theatre and festivals. We also revisit the controversial issue of ‘fun’ in science communication.

Robot Ethics

Winfield, A. F. (2016) Written evidence submitted to the UK Parliamentary Select Committee on Science and Technology Inquiry on Robotics and Artificial Intelligence. Discussion Paper. Science and Technology Committee (Commons), Website. Available from: http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/29428

This is a slightly unusual publication; here Professor Alan Winfield tells the story behind it. In March 2016 the UK Parliamentary Select Committee on Science and Technology opened an inquiry on Robotics and Autonomous Systems they posed four questions; the fourth of which held the greatest interest for me: The social, legal and ethical issues raised by developments in robotics and artificial intelligence technologies, and how they should be addressed? Then, in April, I was contacted by the EPSRC RAS UK network and asked if I could draft a response to this question to then form part of their response to the inquiry. This I did, but of course because of the word limit on overall responses, my contribution to the RAS UK submission was, inevitably, very abbreviated. I was also asked by Phil Nelson, CEO of EPSRC, to brief him prior to his oral evidence to the inquiry, which I was happy to do. Following the first oral evidence session I then wrote to the Nicola Blackwood MP, (then) chair of the Select Committee. In response the committee asked if they could publish my full evidence, which of course I was very happy for them to do. My full evidence was published on the committee web pages on 7 June. To compete the story the inquiry published its full report on 13 September 2016, and I was very pleased to find myself quoted in that report. I was equally pleased to see one of my recommendations – that a commission be set up – appear in the recommendations of the final report; of course other evidence made the same recommendation, but I hope my evidence helped!

Our public engagement projects also influence research as this paper by the Eurathlon consortium shows. The paper reports on the advancement of the field of robotics achieved through the Eurathlon competition:

Winfield, A. F., Franco, M. P., Brueggemann, B., Castro, A., Limon, M. C., Ferri, G., Ferreira, F., Liu, X., Petillot, Y., Roning, J., Schneider, F., Stengler, E., Sosa, D. and Viguria, A. (2016) euRathlon 2015: A multi-domain multi-robot grand challenge for search and rescue robots. In: Alboul, L., Damian, D. and Aitken, J. M., eds. (2016) Towards Autonomous Robotic Systems. (9716) Springer, pp. 351-363. Available from: http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/29283

“Fun” in science communication

The following two publications are the same text published in two different books (with permission). The chapters summarise the views of the authors, including our own Dr Erik Stengler, about the use of fun in science communication, and specifically in science centres.

Viladot, P., Stengler, E. and Fernández, G. (2016) From fun science to seductive science. In: Kiraly, A. and Tel, T., eds. (2016) Teaching Physics Innovatively 2015. ELTE University. ISBN 9789632848150 Available from: http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/27793

Viladot, P., Stengler, E. and Fernández, G. (2016) From “fun science” to seductive science. In: Franche, C., ed. (2016) Spokes Panorama 2015. ECSITE, pp. 53-65. Available from: http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/29105

Both of these are related to a rather controversial blogpost hosted on the SCU blog. That post was selected for publication in a book that captures a collection of thought-provoking blog posts from the Museum field all over the world. In it Erik expressed in a more informal and provocative manner the ideas in the above papers.

Stengler, E. (2016) Science communicators need to get it: Science isn’t fun. In: Farnell, G., ed. (2016) The Museums Blog Book. MuseumsEtc. [In Press] Available from: http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/30360

Science communication through wider cultural activities

A recent commentary explores the factors that contribute to festival goers’ choice to attend science-based events at a summer cultural festival. Presented with a huge variety of interesting cultural events, attendances at science-based events were strong, with high levels of enjoyment and engagement with scientists and other speakers. Our research found out that audiences saw science not as something distinct from “cultural” events but as just another option: Science was culture.

Sardo, A.M. and Grand, A., 2016. “Science in culture: audiences’ perspective on engaging with science at a summer festival”. Science Communication Vol. 38(2) 251–260.

This is a paper on science communication through online videos, long awaited by the small community of researchers working on this specific field who met at the conference above. It reports research conducted by interviewing the people behind the most viewed and relevant UK-based science channels in YouTube. One clear conclusion is that whilst all are aware of the great potential of online video with respect to TV broadcasting, only a few, mainly the BBC, has the insight and the means to realise it in full:

Erviti, M. d. C. and Stengler, E. (2016) Online science videos: An exploratory study with major professional content providers in the United Kingdom. Journal of Science Communication. [In Press] Available from: http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/30236

One area we are interested in is the impact of cultural events on the audience. In this recent paper, we explore the impact of a performance about haematological stem cell transplant on two key audiences: haematology nursing staff and transplant patients. The article suggests that this type of performance is beneficial to both groups, encouraging nursing staff to think differently about their patients and allowing patients to reflect on their past experience in new ways.

Weitkamp, E and Mermikides, A. (2016). Medical Performance and the ‘Inaccessible’ experience of illness: an Exploratory Study, Medical Humanities, 42:186- 193. http://mh.bmj.com/content/42/3/186 (open access)

We’re also very pleased to highlight a publication arising from a student final year project. This was first presented at an international conference in Budapest. It presents the results of a study of the Physics and Astronomy content of At-Bristol in relation to the national curriculum:

Stengler, E. and Tee, J. (2016) Inspiring pupils to study Physics and Astronomy at the science centre at-Bristol, UK. In: Kiraly, A. and Tel, T., eds. (2016) Teaching Physics Innovatively 2015. ELTE University. ISBN 9789632848150 Available from: http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/28122

As we are keen to share our learning more widely, we also occasionally report from conferences. This report, published in JCOM, summarizes highlights of the sessions Erik attended at the 15th Annual STS conference in Graz. It focuses on sessions relevant to robotics and on science communication through online videos, the latter being the session where Erik presented a paper (see next item below):

Stengler, E. (2016) 15th annual STS Conference Graz 2016. Journal of Science Communication. ISSN 1824-2049 Available from: http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/29106

We hope that you find our work interesting and insightful – details of all our publications to date can be found on the Science Communication Unit webpages.

New and notable – selected publications from the Science Communication Unit

The last 6 months have been a busy time for the Unit, we are now fully in the swing of the 2016/17 teaching programme for our MSc Science Communication and PgCert Practical Science Communication students, we’ve been working on a number of exciting research projects and if that wasn’t enough to keep us busy, we’ve also produced a number of exciting publications.

We wanted to share some of these recent publications to provide an insight into the work that we are involved in as the Science Communication Unit.

Science for Environment Policy

Science for Environment Policy is a free news and information service published by Directorate-General Environment, European Commission. It is designed to help the busy policymaker keep up-to-date with the latest environmental research findings needed to design, implement and regulate effective policies. In addition to a weekly news alert we publish a number of longer reports on specific topics of interest to the environmental policy sector.

Recent reports focus on:

Ship recycling: The ship-recycling industry — which dismantles old and decommissioned ships, enabling the re-use of valuable materials — is a major supplier of steel and an important part of the economy in many countries, such as Bangladesh, India, Pakistan and Turkey. However, mounting evidence of negative impacts undermines the industry’s contribution to sustainable development. This Thematic Issue presents a selection of recent research on the environmental and human impacts of shipbreaking.

Environmental compliance assurance and combatting environmental crime: How does the law protect the environment? The responsibility for the legal protection of the environment rests largely with public authorities such as the police, local authorities or specialised regulatory agencies. However, more recently, attention has been focused on the enforcement of environmental law — how it should most effectively be implemented, how best to ensure compliance, and how best to deal with breaches of environmental law where they occur. This Thematic Issue presents recent research into the value of emerging networks of enforcement bodies, the need to exploit new technologies and strategies, the use of appropriate sanctions and the added value of a compliance assurance conceptual framework.

Synthetic biology and biodiversity: Synthetic biology is an emerging field and industry, with a growing number of applications in the pharmaceutical, chemical, agricultural and energy sectors. While it may propose solutions to some of the greatest challenges facing the environment, such as climate change and scarcity of clean water, the introduction of novel, synthetic organisms may also pose a high risk for natural ecosystems. This future brief outlines the benefits, risks and techniques of these new technologies, and examines some of the ethical and safety issues.

Socioeconomic status and noise and air pollution: Lower socioeconomic status is generally associated with poorer health, and both air and noise pollution contribute to a wide range of other factors influencing human health. But do these health inequalities arise because of increased exposure to pollution, increased sensitivity to exposure, increased vulnerabilities, or some combination? This In-depth Report presents evidence on whether people in deprived areas are more affected by air and noise pollution — and suffer greater consequences — than wealthier populations.

Educational outreach

We’ve published several research papers exploring the role and impact of science outreach. Education outreach usually aims to work with children to influence their attitudes or knowledge about STEM – but there are only so many scientists and engineers to go around. So what if instead we influenced the influencers? In this publication, Laura Fogg-Rogers describes her ‘Children as Engineers’ project, which paired student engineers with pre-service (student) teachers.

Fogg-Rogers, L. A., Edmonds, J. and Lewis, F. (2016) Paired peer learning through engineering education outreach. European Journal of Engineering Education. ISSN 0304-3797 Available from: http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/29111

Teachers have been shown in numerous research studies to be critical for shaping children’s attitudes to STEM subjects, and yet only 5% of primary school teachers have a STEM higher qualification. So improving teacher’s science teaching self-efficacy, or the perception of their ability to do this job, is therefore critical if we want to influence young minds in science.

The student engineers and teachers worked together to perform outreach projects in primary schools and the project proved very successful. The engineers improved their public engagement skills, and the teachers showed significant improvements to their science teaching self-efficacy and subject knowledge confidence. The project has now been extended with a £50,000 funding grant from HEFCE and will be run again in 2017.

And finally, Dr Emma Weitkamp considers how university outreach activities can be designed to encourage young people to think about the relationships between science and society. In this example, Emma worked with Professor Dawn Arnold to devise an outreach project on plant genetics and consider how this type of project could meet the needs of both teachers, researchers and science communicators all seeking (slightly) different aims.

A Cross Disciplinary Embodiment: Exploring the Impacts of Embedding Science Communication Principles in a Collaborative Learning Space. Emma Weitkamp and Dawn Arnold in Science and Technology Education and Communication, Seeking Synergy. Maarten C. A. van der Sanden, Delft University of Technology, The Netherlands and Marc J. de Vries (Eds.) Delft University of Technology, The Netherlands.

We hope that you find our work interesting and insightful, keep an eye on this blog – next week we will highlight our publications around robots, robot ethics, ‘fun’ in science communication and theatre.

Details of all our publications to date can be found on the Science Communication Unit webpages.

Postgraduate Science Communication students get stuck in on ‘Science in Public Spaces’

Emma Weitkamp & Erik Stengler

September saw the lecturing staff at the Science Communication Unit welcoming our new MSc Science Communication and PgCert Practical Science Communication students to UWE and Bristol. It also sees the start of our refreshed programme offering, which includes significant changes and updates to two of our optional modules: Science in Public Spaces and Science on Air and On Screen.

The first three-day block of Science in Public Spaces (SiPS) marks the start of a diverse syllabus that seeks to draw together themes around face-to-face communication, whether that takes place in a what we might think of as traditional science communication spaces: museums, science centres and festivals or less conventional spaces, such as science comedy, theatre or guided trails. Teaching is pretty intense, so from Thursday, 29th September to Saturday, 1st October, students got stuck into topics ranging from the role of experiments and gadgets to inclusion and diversity.

Practical science fair

Thursday, 29th September saw the 13 SiPS students matched with researchers from the Faculty of Health and Applied Sciences. Students were introduced to cutting edge research and have been challenged to think about how this could be communicated to the public in a science fair setting. Each student will work with their researcher to create a hands-on activity which they will have the opportunity to deliver to the public at a science fair to be held during a University Open Day in the spring.

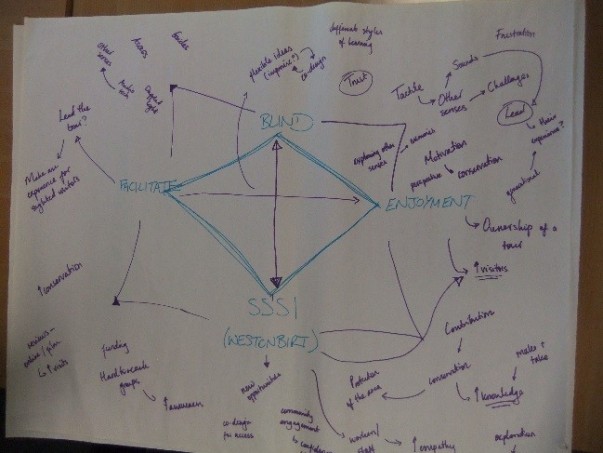

Towards the end of the three days a session on creativity generated intense discussion about how we might judge what creativity is through to practical techniques and tips we might use to stimulate creative thinking. The session included a word diamond (McFadzean, 2000), where groups considered how you might foster engagement and enjoyment amongst blind visitors to the Grand Canyon, how blind visitors could be involved in creating a sensory trail (for sighted people) at an arboretum or how to enable a local community to be involved in decision making around land use that involved ecosystem services trade-offs. Challenging topics that draw on learning from earlier in the week.

After a final session on connecting with audiences, students (and staff) were looking a little tired; three days of lectures, seminars and workshops is exhausting. We hope students left feeling challenged, excited and ready to start exploring this new world of science communication and public engagement and that they find ways to connect their studies with events and activities they enjoy in their leisure time – though that might not apply to the seminar reading!

Science in Public Spaces got off to an excellent start, thanks to the students for their engaged and thoughtful contributions in class. Up next is the Writing Science module, where Andy Ridgway, Emma Weitkamp and a host of visiting specialists will be introducing students to a wide range of journalistic techniques and theories. Then it will be the turn of the new Science on Air and on Screen where Malcolm Love will introduce students to techniques for broadcasting science whether on radio, TV or through the range of digital platforms now open to science communicators. Looks to be an exciting year!

McFadzean, E. (2000) Techniques to enhance creativity. Team Performance Management: An International Journal, 6 (3/4) pp. 62 – 72

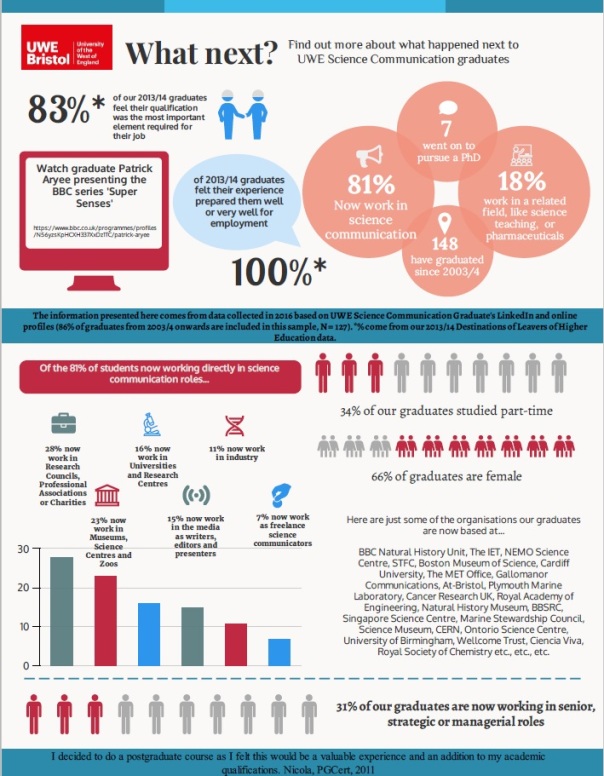

What happens to sci comms graduates?

Lots of people are interested to find out what our Masters in Science Communication and Postgraduate Certificate in Practical Science Communication students at UWE, Bristol get up to when they leave us. As the infographic shows, it’s pretty impressive. We’re currently advertising part-bursaries to study with us in 2016/17, if you’d like more info contact Clare.Wilkinson@uwe.ac.uk

You can download a pdf of this infographic: Sci Comm UWE Graduate Destination Infographic 2016

Clare Wilkinson, the programme leader, will be presenting some of this information at next week’s PCST Annual Conference.

Behind the scenes at Bristol Museum

Text by Andy Ridgway, Senior Lecturer in Science Communication, images by Marta Palau Franco, euRathlon project manager.

“Artists love this kind of thing,” says Bonnie Griffin, Natural History Curator at Bristol Museum & Art Gallery. The thing in question is a scrawny-looking taxidermy pigeon that’s a victim of moth strike. The moths have stripped away the ‘feathery bits’ of its feathers, the barb, to reveal the rachis – the pointy bits in the middle.

He – or she – was introduced to students on our Masters and Postgraduate Certificate in Science Communication during our tour of the Museum’s natural history store, somewhere that’s normally off limits to members of the public. The tour was part of a day spent at the Museum to get an insight into the inner workings of a museum with a vast natural history collection.

Natural History Curator Bonnie Griffin shows our MSc students some of the extraordinary taxidermy in the natural history store

The pigeon may be one of the less exotic residents of the store but it illustrates the two principle challenges of having such a huge resource; how to make use of a valuable resource when display space is at such a premium and how to stop the objects themselves being eaten or decaying in some other way.

The store has 650,000 residents – all of them dead – and this represents 90-95 per cent of Bristol Museum’s natural history collection. This means there’s only space for 5-10 per cent of the collection to be on display at any one time. It’s not an uncommon problem (and has prompted some at other institutions to consider drastic action).

But ways are being found for the store’s residents to earn their keep. So while the scrawny pigeon is making its living as an artist’s muse (the shiny tropical beetles are popular too), other residents are the object of scientific study. A humming bird, for instance, is giving us a clearer picture of what dinosaur plumage was like – apparently the way the colour and shine are created is the same as would have been the case in dinosaur feathers.

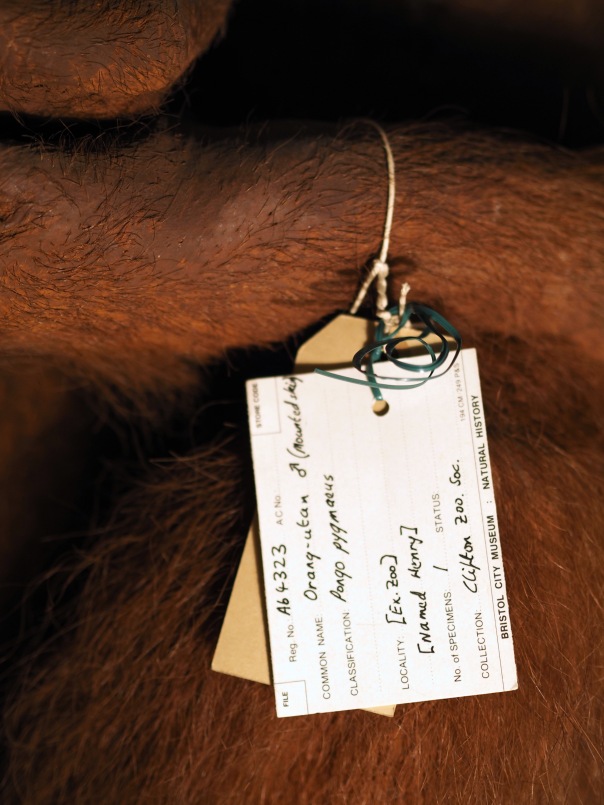

Mysterious samples make up some of the 650,000 items in the collection

It is Bristol’s history that has led to such a vast collection – its wealthy merchants of past years would pay for specimens from exotic lands to be brought to our shores. And the museum’s proximity to Bristol Zoo is another factor – several of the zoo’s inhabitants have taken up residence in the museum once they have died. Among them is Henry the orangutan, who once shared a cage with his orangutan sweetheart, Ann, at the zoo. Today, the store is taking in fewer new residents and rather than coming from far flung corners of the globe, most of it is roadkill.

Henry the orangutan, formerly a resident of Bristol Zoo.

While moth strike is one of the threats to the natural history collection, pyrite decay (where the sulphite component of the mineral oxidises) is one of the – if not the – biggest threats to the collection in the museum’s geology store. So temperature and humidity down here are continually monitored. In the geology store we were given a guided tour by Senior Natural History Curator Dr Victoria Purewal.

Again it’s the detail known about some of the objects that helps bring them back to life. Take fossil of Pliosaurus carpenteri, that sits on one of the shelves and is the only known example of this species (it’s named after Simon Carpenter, who discovered it at Westbury clay pit in Wiltshire). Thought to be a female, it would have suffered from excruciating toothache in the final years of its life – its fossilised remains revealing signs of a tooth abscess.

Shelves of fossils, some of them unique finds, in the Bristol Museum store.

Thanks to the staff at the museum for such a fascinating insight into their work – it was a valuable day out for our students.

Masters and beyond with the SCU

Clare Wilkinson explains some of the programmes that UWE Bristol offers in Science Communication, and how coming back to school builds towards the ‘university of life.’

This year we had around 25 new students joining us to start our MSc Science Communication programme and Postgraduate Certificate in Practical Science Communication.

MSc student discusses a project during a UWE open day

At postgraduate level we work with students in a number of ways. Most students join our MSc Science Communication programme, as either a full or part-time student. Running for over ten years this programme has developed an excellent reputation for its combination of theory and practice. This means it continues to attract both those who have just completed a university degree and have already made the decision that their future lies in science communication, as well as students who have been working in a related field for a while and either are looking to make a career transition or to firmly establish a more formal qualification.

Running for over ten years this programme has developed an excellent reputation for its combination of theory and practice.

We also have a smaller number of students who take our Postgraduate Certificate in Practical Science Communication. Typically students on this programme tend to be practicing researchers who have been communicating their own research alongside their ‘day job’ and are looking to develop that experience further. On similar lines we also have a number of PhD students, from a wide range of areas at UWE, who are taking one or two of our science communication modules as part of their PhD programme. It’s fantastic to see early career researchers identifying a role for communication and engagement and building this into their research from the outset.

I tend to think about the programme in three ways; as ‘back to school’, the ‘light bulb’ moment and the ‘university of life’.

Back to school

As programme leader I tend to be in touch with our new students a lot, even before they start their courses. I’ll be confirming people’s module choices, double checking they are on the right programme and often having last minute meetings to let new students, and sometimes their families, get a feel for our campus and team.

Deciding to undertake postgraduate study is a big commitment, intellectually but also from a time and financial perspective, and so it’s understandable that often our students, their partners and families can feel a little nervous about it. I vividly remember once having to explain the potential job prospects of our course to an applicant’s father. Science communication was new to him and he wanted to be 100% sure it would offer his science graduate son a potential route to his desired employment in the future. I’m also well practiced in finding the odd coloured pen or piece of paper for a restless five-year old accompanying their parent to a UWE open evening, with very little interest in the new MSc their caregiver is about to undertake.

Any fearfulness will turn to smiles. A realisation takes hold that they have found a place where everyone shares their interests.

So, whatever the age, circumstances or commitments of our new students, starting a postgraduate programme will often mean change, uncertainty and challenges. My aim is that by the first day all new students feel confident that they have made the right decision for them, so that the ‘back to school’ feeling is one they (and their families) can embrace.

The light bulb moment

The start of the programme is always really busy, and this year was no different. Amongst registration activities, introductions to the library and the practicalities of life as a UWE student we also try to fit in content about life as a science communicator, and importantly, lots of opportunities for our students to meet and talk with each other. You only need to look around the room on the first day to realise that people are feeling nervous, anticipating what they will have in common with their new peers and eyeing up those they might potentially be friends with. This brings me to the light bulb moment.

We get introductions happening straight away… ‘Tell us about yourself’, I will say to each person, ‘just some snippets about you, where you are from and why you are here’. It’s then that it starts, each person around the room expressing their passion for communicating, that they love their subject (whatever that might be – we don’t only accept only science-based students on our programme), but that they think their real strengths lie in engaging around it. And one after another, any fearfulness will turn to smiles. A realisation takes hold that they have found a place where everyone shares their interest in communicating and that this will be their home for the coming weeks, months or years.

The university of life

On the first day, we distribute module guides and assessment information, talk about the various disciplines that influence science communication, and outline the expected level of reading. It will become clear that no student can learn all that there is to know about science communication in the first days or weeks of teaching and that much, much more is to come. As one door has closed on their undergraduate studies, the possibilities at Masters level can seem endless. It can be overwhelming, but as with the start of any new project the possibilities are exciting.

If you are interested in finding out more about the UWE Bristol Science Communication Masters or Postgraduate Certificate, please go to our website.