Blog Archives

Science communication: people, projects, events 2017

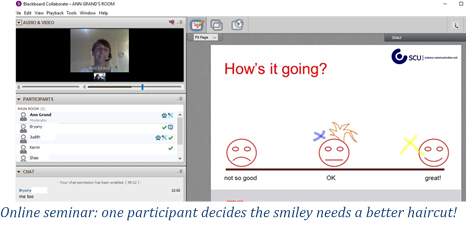

Our Science Communication Masterclass has been running very successfully for quite a few years now and like my colleagues, I’ve had happy times running workshops, and met some really interesting participants. But we were never able to squeeze everyone in who wanted to come, while others were unable to travel to the UK.

We decided to meet this challenge by creating an online professional development  course – Science communication: people, projects, events – targeted at people who wanted to develop their skills and knowledge of science communication. Participants have joined us from far and near: across the UK, from Uganda, Switzerland, Portugal, Australia, Brazil, Canada and more.

course – Science communication: people, projects, events – targeted at people who wanted to develop their skills and knowledge of science communication. Participants have joined us from far and near: across the UK, from Uganda, Switzerland, Portugal, Australia, Brazil, Canada and more.

They’ve been a real mix: recent science graduates, museum professionals, communications people, people working in institutions, large corporations, small businesses and start-ups. Some have experience of public engagement but for some, the course opens a new horizon:

… in my heart I believe I found a new passion – science communication!

We ran the first course in 2015. Naturally, as good public engagement practitioners, we ask the participants to reflect on and evaluate the course each time it is presented and we have used their feedback to refine and develop the course.

In the first year, participants felt that the time demands were a little onerous for people working full-time, so in 2016 and 2017, we built in two study breaks to allow participants to draw breath and catch up on content they might have missed. Unfamiliar tools caused some puzzlement, so we created micro-videos to show participants how to use forums, wikis and other learning tools. We also created a special LinkedIn group for course ‘graduates’ because participants really wanted to maintain the relationships that develop:

It would be great to be able to keep in touch with fellow participants and tutors.

The course now runs in eight units over ten weeks, with one or two members of the SCU tutoring each unit. In 2016 and 2017, I led the course from my current base in Perth, Western Australia. One of the virtues of working online: on the Internet, no one knows you’re on the beach!

We present the course materials using a mixture of guided self-directed learning activities, reading, narrated presentations, forums, wikis, vlogs and online seminars. Other than the seminars, participants are able to fit their engagement around their work and other commitments. Participants like the variety of methods:

We present the course materials using a mixture of guided self-directed learning activities, reading, narrated presentations, forums, wikis, vlogs and online seminars. Other than the seminars, participants are able to fit their engagement around their work and other commitments. Participants like the variety of methods:

forums: an ‘excellent way to discuss ideas despite not meeting other coursemates in person’

webinars: an ‘opportunity to put voices to names’ and ‘a great experience’

wikis: ‘pushed [me] to develop an idea for a project’ and get ‘lots of feedback and input from other participants and the tutors’

The online environment offers us so many opportunities to reach out to scientists, science communicators and public engagement people around the world and welcome them to the SCU family. In 2016, we created a companion online course focussing on Online and Media Writing, which is currently in its second presentation.

Feedback from this year’s participants is still being reviewed but I’m sure it will give us food for thought and ways to improve. We hope we’ll be welcoming lots more participants in 2018!

Please visit our website for further details of our online courses.

Ann Grand

FET Award: STEM outreach at Luckwell Primary

This year, I have been lucky enough to receive a FET Award to promote STEM at a local primary school in south Bristol. Our key aims have been to use the expertise of UWE staff and students to deliver events which not only encourage children to pursue STEM careers, but also support teachers with some of the harder to achieve National Curriculum objectives.

Our first activity involved all students in Key Stage 2 – 120 in total. Inspired by the LED cards on Sparkfun, and ably assisted by fellow FARSCOPE students Hatem and Katie, we ran a lesson in which students used copper tape, LEDs and coin cell batteries to create a light-up Christmas tree or fire-side scene. Our aim was not only to show the students that electronics is fun and accessible, but to re-reinforce the KS2 National Curriculum objectives relating to electricity and conductivity.

Although a little hectic, the students really enjoyed the task and the teachers felt that the challenge of interacting with such basic components (as opposed to more “kid friendly” kits), really helped to drive home our lesson objectives.

To re-reinforce the Christmas card activity, we also ran a LED Creativity contest over the Christmas break. Students were given a pack containing some batteries, LEDs and copper tape and tasked with creating something cool.

Entries ranged from cameras with working flash to scale replicas of the school. The full range of entries and winners can be found here. Overall, we were blown away by the number and quality of the entries.

Our second focus was introducing students to programming. To this end, we have been running a regular code club every Monday, this time supported by volunteers from UWE alongside FARSCOPE student Jasper. In code club, we use a mix of materials to introduce students to the programming language scratch. We currently have 16 students attending each week and recently were lucky enough to receive a number of BBC Micro bits.

Alongside Code club, we also ran a workshop with the Year 5 class, to directly support the national curriculum objectives related to programming. Students were given Tortoise robots (Built by FARSCOPE PhD students, in honour of some of the very first autonomous robots, built in Bristol by Grey Walter). Children had to program and debug an algorithm capable of navigating a maze.

As the outreach award comes to an end, we are planning a final grand event. Each year the students at Luckwell School get to spend a week learning about real-life money matters in “Luckwell Town”. During this week, students do not attend lessons – instead, they can choose to work at a number of jobs to earn Luckwell Pounds. This year, we will be supporting Luckwell Town by helping to run a Games Development studio. Students will use Scratch to design and program simple games for other students to play in the Luckwell Arcade.

As with our prior events, the success will depend on volunteers from UWE donating their time and expertise to support us.

Luckwell Town will take place every morning of the week commencing June 12th. We are looking for volunteers to support us, so please respond to the Doodle poll if you are interested.

Martin Garrad, PhD student in robotics

SynBio – in need of public engagement

In a recent book review for JCOM, I outlined a few of the ethical, social and legal issues that make synthetic biology a potentially fascinating topic from a public engagement perspective. ‘Synthetic Biology Analysed’ (Englehard, 2016) draws together contributions from experts in ethics, law, risk analysis and sociology. In doing so, it provides a fairly accessible discussion of the nature of synthetic biology – what the field encompasses and how we might think about different types of synthetic biology (from those that are essentially developments of genetic engineering to approaches that incorporate non-naturally occurring nucleotides (components of DNA)). These raise different challenges when it comes to assessing risk, for example to the environment, posed by these developments.

Shortly after reading Englehard’s (2016) book, I had the opportunity to explore synthetic biology further, through a participatory theatre project – Invincible – initiated by the University of Bristol’s SynBio group and produced by Kilter theatre company. Both Englehard’s book and ‘Invincible’ the theatre production point to a need for public engagement in this area.

Speaking to the members of the Invincible production team, I learned much about the process of developing this work and the learning curve that had to be climbed in order to understand the research. Kilter were also keen to address other STEM issues, such as presenting women as scientists to counter gender stereotypes.

One aspect of the performance I found particularly refreshing was the way that actual researchers were included. They may not have had ‘acting’ roles, but they were present throughout and engaged in discussion with the audience at the end of the performance (when their presence was revealed). Their inclusion, and the setting of the performances in a flat both worked to highlight the pervasiveness of science in our lives.

In a chapter focusing specifically on public engagement in Synthetic Biology Analysed, Pardo and Hagen point out the low salience of synthetic biology with the public. While this is not uncommon, with many scientific topics taking place silently and behind closed doors, the potential impacts (social and environmental) of synthetic biology highlighted in Englehard’s book suggest it is time for a public discussion. It is nice to see that University of Bristol’s SynBio group are beginning to hold this conversation.

ENGELHARD, M. ED. (2016). SYNTHETIC BIOLOGY ANALYSED: TOOLS FOR DISCUSSION AND EVALUATION. SPRINGER INTERNATIONAL.

Emma Weitkamp

New and notable – selected publications from the Science Communication Unit

The last 6 months have been a busy time for the Unit, we are now fully in the swing of the 2016/17 teaching programme for our MSc Science Communication and PgCert Practical Science Communication students, we’ve been working on a number of exciting research projects and if that wasn’t enough to keep us busy, we’ve also produced a number of exciting publications.

We wanted to share some of these recent publications to provide an insight into the work that we are involved in as the Science Communication Unit.

Science for Environment Policy

Science for Environment Policy is a free news and information service published by Directorate-General Environment, European Commission. It is designed to help the busy policymaker keep up-to-date with the latest environmental research findings needed to design, implement and regulate effective policies. In addition to a weekly news alert we publish a number of longer reports on specific topics of interest to the environmental policy sector.

Recent reports focus on:

Ship recycling: The ship-recycling industry — which dismantles old and decommissioned ships, enabling the re-use of valuable materials — is a major supplier of steel and an important part of the economy in many countries, such as Bangladesh, India, Pakistan and Turkey. However, mounting evidence of negative impacts undermines the industry’s contribution to sustainable development. This Thematic Issue presents a selection of recent research on the environmental and human impacts of shipbreaking.

Environmental compliance assurance and combatting environmental crime: How does the law protect the environment? The responsibility for the legal protection of the environment rests largely with public authorities such as the police, local authorities or specialised regulatory agencies. However, more recently, attention has been focused on the enforcement of environmental law — how it should most effectively be implemented, how best to ensure compliance, and how best to deal with breaches of environmental law where they occur. This Thematic Issue presents recent research into the value of emerging networks of enforcement bodies, the need to exploit new technologies and strategies, the use of appropriate sanctions and the added value of a compliance assurance conceptual framework.

Synthetic biology and biodiversity: Synthetic biology is an emerging field and industry, with a growing number of applications in the pharmaceutical, chemical, agricultural and energy sectors. While it may propose solutions to some of the greatest challenges facing the environment, such as climate change and scarcity of clean water, the introduction of novel, synthetic organisms may also pose a high risk for natural ecosystems. This future brief outlines the benefits, risks and techniques of these new technologies, and examines some of the ethical and safety issues.

Socioeconomic status and noise and air pollution: Lower socioeconomic status is generally associated with poorer health, and both air and noise pollution contribute to a wide range of other factors influencing human health. But do these health inequalities arise because of increased exposure to pollution, increased sensitivity to exposure, increased vulnerabilities, or some combination? This In-depth Report presents evidence on whether people in deprived areas are more affected by air and noise pollution — and suffer greater consequences — than wealthier populations.

Educational outreach

We’ve published several research papers exploring the role and impact of science outreach. Education outreach usually aims to work with children to influence their attitudes or knowledge about STEM – but there are only so many scientists and engineers to go around. So what if instead we influenced the influencers? In this publication, Laura Fogg-Rogers describes her ‘Children as Engineers’ project, which paired student engineers with pre-service (student) teachers.

Fogg-Rogers, L. A., Edmonds, J. and Lewis, F. (2016) Paired peer learning through engineering education outreach. European Journal of Engineering Education. ISSN 0304-3797 Available from: http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/29111

Teachers have been shown in numerous research studies to be critical for shaping children’s attitudes to STEM subjects, and yet only 5% of primary school teachers have a STEM higher qualification. So improving teacher’s science teaching self-efficacy, or the perception of their ability to do this job, is therefore critical if we want to influence young minds in science.

The student engineers and teachers worked together to perform outreach projects in primary schools and the project proved very successful. The engineers improved their public engagement skills, and the teachers showed significant improvements to their science teaching self-efficacy and subject knowledge confidence. The project has now been extended with a £50,000 funding grant from HEFCE and will be run again in 2017.

And finally, Dr Emma Weitkamp considers how university outreach activities can be designed to encourage young people to think about the relationships between science and society. In this example, Emma worked with Professor Dawn Arnold to devise an outreach project on plant genetics and consider how this type of project could meet the needs of both teachers, researchers and science communicators all seeking (slightly) different aims.

A Cross Disciplinary Embodiment: Exploring the Impacts of Embedding Science Communication Principles in a Collaborative Learning Space. Emma Weitkamp and Dawn Arnold in Science and Technology Education and Communication, Seeking Synergy. Maarten C. A. van der Sanden, Delft University of Technology, The Netherlands and Marc J. de Vries (Eds.) Delft University of Technology, The Netherlands.

We hope that you find our work interesting and insightful, keep an eye on this blog – next week we will highlight our publications around robots, robot ethics, ‘fun’ in science communication and theatre.

Details of all our publications to date can be found on the Science Communication Unit webpages.

What IS storytelling? What IS NOT storytelling?

What IS storytelling? What IS NOT storytelling? These two questions opened the 9th conference on “Storytelling: Global Reflections on Narrative” I attended from the 10th to the 12th of July in Oxford (UK). As participants, we were asked to reply, and we gave completely different answers, depending on our academic field and personal experience.

We defined storytelling as an engaging and dynamic form of communication, which must not be boring at all. Moreover, we emphasised the fact that storytelling does not include only what is told, but also what is kept silent, what is not remembered, and what is changed, and that it encompasses many points of view, many different stories, and many different ways of telling the same story.

During the conference, each speaker contextualised storytelling in a different field: literature, history, sociology, communication, education, sciences, and even medicine; and we discussed the topic taking into account professional and personal experiences as well, thus getting a broad and inclusive overview of storytelling.

Storytelling is not only influenced by the discipline in which it’s studied or applied, but also by many other factors, such as background, culture, education, ethnicity, nationality, social class, gender, and age of storytellers and of the audiences.

Novels, advertisements, TV shows, etc. communicate a story using language, semiotic signs, stereotypes, metaphors, and rhetoric figures that are tailored for specific target publics. Moreover, stories usually reflect the social values and characteristics of the audiences. For example, in Japanese anime the homogeneity of the Japanese society is represented by the possibility each character has to become the protagonist of the story, whereas individualistic feature of the Western societies is depicted by the presence of only one main character in Western comics.

Medium may change the way we tell or listen to a story. We read novels in a sequential way, page after page from the beginning to the end, whereas we can read a story on social media in a relational way (as in mind mapping), jumping from one point to any other as we please. Moreover, in digital interactive documentaries and videogames, we (as audience) can even change the story.

Storytelling also differs in its applications: we can use it for conveying information or entertaining, but we can also use it for advocacy campaigns, education, and research. Indeed, storytelling can be a suitable technique for advocacy, due to its capability of engaging audiences emotionally and personally, and it is effective in involving students in school lessons as well, and in stimulating their critical thinking, communication and writing skills, creativity etc.

The use of storytelling in the research field is particularly interesting. By analysing either ancient books or new TV fictions, we can investigate the individual characteristics of authors as well as well the social beliefs, values, and imaginary of a specific historical period, and we can study how they changed over time. We can acquire similar data by collecting witnesses’ stories of a specific event, as well as asking the research subjects to write a narrative on a specific issue. For example, patients’ stories on how they perceive their disease and how it is affecting their quality of life can provide further information to improve our comprehension of the disease from a clinical point of view, understand patient-physician communication, or improve the health care system. Even collecting stories on digital media and videogames we can yield insights on individuals and social groups’ characteristics.

What is storytelling? What is not storytelling? Though it may be very difficult to give a concise and inclusive answer to these questions, we can say that storytelling provides many different opportunities and challenges in science and health communication as well as in research.

Find out more about the conference ‘Storytelling: Global Reflections on Narrative‘

Elena Milani – PhD student, Science Communication Unit.

The long and winding road to science journalism

How do you get your first job in science communication? That’s not a straightforward question to answer – when it comes to science journalism at least. My experience of working in the industry showed me that having some kind of experience – either in the form of a placement or a few articles published – can be invaluable. Just as important as any qualification, in fact. And if you’ve won some form of recognition for your writing – perhaps through a competition – that can have a big impact on your job prospects too. It’s probably not too much of an exaggeration to say that there are as many routes into science writing as there are science writers.

It’s out of this experience that the UWE SCU Science Writing Competition was born. Targeted specifically at those who haven’t had popular science writing published before, it is now in its second year.

Given its target audience of new writers, this year we (the SCU that is) decided to provide writing advice in the form of blogs from the judges and other respected science writers, including one of last year’s winners – Emily Coyte .

There were another couple of important additions too, including a partnership with the Royal Institution – an organisation with a track record for nurturing new talent – and a survey of the competition participants aimed at gaining a fuller picture of the opportunities and barriers they face in breaking in to the science writing industry. The survey makes for interesting reading.

For starters, all of the 49 people who took part in the survey (out of roughly 90 competition entries) said they were interested in a career in science writing in some form – some as full time writers or editors and others envisaged writing as a sideline to a career in research science. Many participants were students and most (almost 90%) had not had any form of science writing training. Of those who hadn’t had training, a fairly high proportion (45%) said they were not aware of any training courses.

However, it’s where the responses to this survey – from those who want to be science writers – are compared with the responses from another survey we conducted – from those who are already science writers – that things get really interesting. But this isn’t the place to go into any detail on that – there will be more on that later. So watch this space…

As for this year’s science writing competition, the shortlist has now been drawn up and the judges will meet in August to decide the winners, who will be announced on 1 September 2016.

Andy Ridgway

Baby-led, puree, Annabel Karmel and me? When science impacts on the choices we make in parenting

How we make choices as consumers, patients, parents and members of the public has, of course, long been of interest to science communicators, and topics like immunisation can continue to raise differences in perspectives, as well as media interest. A few years ago we started to think about the sometimes challenging process of weaning a baby. Ruth had recently had two young children herself, whilst completing her MSc Science Communication with us, and I’d been doing some research with parents and caregivers in community groups, so we knew weaning was a topic that was being discussed. But what about the parents who might not be out there in these social spaces, what was happening online? We asked the question ‘how do people on Mumsnet frame media coverage of weaning?’

As our starting point we considered a review of scientific evidence published in the British Medical Journal in 2011. This work, by Fewtrell and colleagues, suggested the period of exclusive breastfeeding recommended by the World Health Organisation be reduced from six months to four. Unsurprisingly the study attracted media attention, particularly in ‘quality’ newspapers like The Times, The Guardian, and especially, The Telegraph, and was frequently reported on by specialist health and science correspondents. They tended to talk about ‘risk’ but rarely contextualised that with further information on the study itself.

On Mumsnet it was clear that a vibrant community was keen to discuss the issue of weaning, and we located 112 comments that directly referred to the Fewtrell example and its media coverage. What were people most wanting to talk about? The inaccuracy of media coverage really stood out in their comments, as well as frustration that it was returning to the breast vs. bottle aspects of the debate. And the forum discussions often presented more context, nuances around the question of ‘risk’ and the details of the study itself. Of course, they had more room to do so, but it was interesting to see these types of details being discussed.

What does this tell us about science, the media and how it’s discussed online? Well it suggests that at least amongst this very small sample of Mumsnet users there is some awareness of the weaknesses that can be present in science and health reporting, but also that people often use scientific and personal information in transitionary means, embellishing some of the deficiencies of media coverage in interesting and new ways. As people become more and more reliant on social media sources for information, further work is needed on how this is supplementing and challenging our relationships with scientific and medical expertise but also how we use our social networks to support decision making. You can find out more about this work in a recent Journalism article or at:

http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/27843/3/The_Worries_of_Weaning_paper_10_10_15%20-%20Copy.pdf

Clare Wilkinson and Ruth Knowles

Tackling the challenge of engaging with drought and frogs

SCU was well represented at the Bristol Festival of Nature (BFON) in June, with Associate Professor Emma Weitkamp manning the Drought Risk and You (DRY) stand on Saturday and MSc student Hannah Conduit showcasing her research with the Durrell Trust as part of UWE’s festival tent.

Emma is exploring communication and engagement barriers and enablers related to drought and water scarcity within the DRY project. At BFON, Emma was interested to hear what visitors think about a set of cartoons produced as part of the project and whether these might be a tool to open conversations about water scarcity; climate change models suggest the UK will have wetter winters and drier summers, increasing the risk that we will have serious droughts. . In the southern UK, the most severe in living memory is the drought of ’76.

Emma is exploring communication and engagement barriers and enablers related to drought and water scarcity within the DRY project. At BFON, Emma was interested to hear what visitors think about a set of cartoons produced as part of the project and whether these might be a tool to open conversations about water scarcity; climate change models suggest the UK will have wetter winters and drier summers, increasing the risk that we will have serious droughts. . In the southern UK, the most severe in living memory is the drought of ’76.

Initial work within the DRY project highlights the challenges of engaging people with Drought. Unlike flooding which has immediate effects, drought has a slow onset and many not have immediate relevance to many people. Rain during BFON highlights the challenge – how do you engage people with drought when it’s raining?

Emma Weitkamp and DRY Project leader Lindsey McEwen at the DRY stand, Bristol Festival of Nature

Emma presented initial work on citizen science aspects of the DRY project at the Society for Risk Analysis meeting in Bath, 20th June, while Adam Corner, of Climate Outreach presented the project’s initial work on communication barriers.

Jeff Dawson with the project research tools

Frogs are not the cuddliest of species, so Hannah is tackling similar challenges through her research with the Durrell Trust. Amphibians have suffered a dramatic decline in numbers, and around 40% of all amphibian species are now considered to be under threat. But in a world of glamorous tigers and cuddly lemurs, it is sometimes hard for frogs to get a look in.

Hannah’s research focuses on one particular species of frog; second largest in the world and perhaps one of the most endangered. The ‘Mountain Chicken’ is aptly named for its meat; prised locally as a delicacy with taste and consistency similar to that of its feathery cousin.

With less than 100 individuals remaining in the wild and continued threat from disease, the Durrell Trust and UWE are working together to find more effective ways of communicating the plight of amphibians like the Mountain Chicken.

At BFON, Hannah and her Durrell supervisor, Jeff, along with a small group of volunteers talked with the public about the Mountain Chicken’s story, as well as showing them some of the methods used by scientists and researchers to monitor the remaining wild frogs. Scanning the stall’s microchipped frog plushies and swabbing them for a fungal disease called Chytrid proved to be the weekend’s most popular activities.

Erik Stengler, Hannah Conduit and Jeff Dawson, at the Saving the Mountain Chicken Frog stand, Bristol Festival of Nature

Research is currently ongoing for Hannah’s project, and will culminate in a handbook for use by the Mountain Chicken Recovery Programme in raising awareness and gathering interest amongst the public for the species.

Blog post written by Emma Weitkamp & Hannah Conduit

An increasing number of academics are using blogs to reach a wider audience and share their research in a more comprehensible way. However, a staggering 81% of people will only read your first paragraph (71% the second, 63% the third and 32% the fourth, you get the idea if you’ve read this far…).

An increasing number of academics are using blogs to reach a wider audience and share their research in a more comprehensible way. However, a staggering 81% of people will only read your first paragraph (71% the second, 63% the third and 32% the fourth, you get the idea if you’ve read this far…).