Blog Archives

SynBio – in need of public engagement

In a recent book review for JCOM, I outlined a few of the ethical, social and legal issues that make synthetic biology a potentially fascinating topic from a public engagement perspective. ‘Synthetic Biology Analysed’ (Englehard, 2016) draws together contributions from experts in ethics, law, risk analysis and sociology. In doing so, it provides a fairly accessible discussion of the nature of synthetic biology – what the field encompasses and how we might think about different types of synthetic biology (from those that are essentially developments of genetic engineering to approaches that incorporate non-naturally occurring nucleotides (components of DNA)). These raise different challenges when it comes to assessing risk, for example to the environment, posed by these developments.

Shortly after reading Englehard’s (2016) book, I had the opportunity to explore synthetic biology further, through a participatory theatre project – Invincible – initiated by the University of Bristol’s SynBio group and produced by Kilter theatre company. Both Englehard’s book and ‘Invincible’ the theatre production point to a need for public engagement in this area.

Speaking to the members of the Invincible production team, I learned much about the process of developing this work and the learning curve that had to be climbed in order to understand the research. Kilter were also keen to address other STEM issues, such as presenting women as scientists to counter gender stereotypes.

One aspect of the performance I found particularly refreshing was the way that actual researchers were included. They may not have had ‘acting’ roles, but they were present throughout and engaged in discussion with the audience at the end of the performance (when their presence was revealed). Their inclusion, and the setting of the performances in a flat both worked to highlight the pervasiveness of science in our lives.

In a chapter focusing specifically on public engagement in Synthetic Biology Analysed, Pardo and Hagen point out the low salience of synthetic biology with the public. While this is not uncommon, with many scientific topics taking place silently and behind closed doors, the potential impacts (social and environmental) of synthetic biology highlighted in Englehard’s book suggest it is time for a public discussion. It is nice to see that University of Bristol’s SynBio group are beginning to hold this conversation.

ENGELHARD, M. ED. (2016). SYNTHETIC BIOLOGY ANALYSED: TOOLS FOR DISCUSSION AND EVALUATION. SPRINGER INTERNATIONAL.

Emma Weitkamp

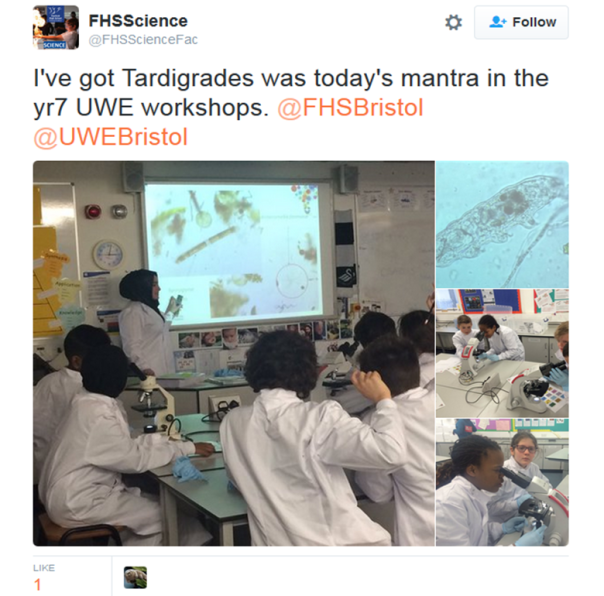

Innovating university outreach

Corra Boushel

Through funding from the Higher Education Funding Council for England and internal backing, the Science Communication Unit has been involved in developing an ambitious new UWE Bristol outreach programme for secondary schools in the region. We’ve worked with over 4,000 school pupils in the last 18 months, finding tardigrades, hacking robots and solving murder mysteries with science, technology, engineering and maths.

The idea behind the project is not only to engage local communities and raise pupil aspirations. Our plan is to refocus outreach within the university so that it no longer competes with student learning or research time, but instead functions to develop undergraduate skills and to showcase UWE Bristol’s cutting edge research.

The outreach activities are developed by specialists, but then led by undergraduate students and student interns, who develop confidence and skills. UWE Bristol students can use their outreach activities to count towards their UWE Futures Award, and in some degree courses we are looking at ways that outreach projects can provide credit and supplement degree modules. Researchers can use the activities to increase their research impact and share their work with internal and external audiences – getting students excited about research through explaining it to young people. Enabling students to lead outreach – including Science Communication Masters and Postgraduate Certificate students – means that the university delivers more activities, reaching more schools and giving more school pupils the chance to participate.

The brainchild of UWE Bristol staff Mandy Bancroft and John Lanham, the development stages of the project have been led by Debbie Lewis and Corra Boushel from the Faculty for Health and Applied Science and the Science Communication Unit with support from Laura Fogg Rogers. The project is now being expanded into a university-wide strategy with cross-faculty support to cover all subject areas, not only STEM.

Special thanks on the project go to all of our student ambassadors and previous interns, as well as our current team of Katherine Bourne, Jack Bevan and Tay-Yibah Aziz. Katherine and Tay-Yibah are employed on the project alongside their studies in the Science Communication Unit.

Special thanks on the project go to all of our student ambassadors and previous interns, as well as our current team of Katherine Bourne, Jack Bevan and Tay-Yibah Aziz. Katherine and Tay-Yibah are employed on the project alongside their studies in the Science Communication Unit.

Communicating research: do we need to be more creative?

Clare Wilkinson and Emma Weitkamp are Associate Professors based at the Science Communication Unit, University of the West of England, Bristol.

A press release and tracking of the resultant media coverage, or a public talk, are relatively easy methods of public communication, which most researchers are comfortable adding to their pathways to impact, but what about those wanting to be a bit more adventurous or wishing to undertake public engagement right from the start to help shape research design or data collection? In our new book Creative Research Communication: Theory and Practice, we explore a range of emerging or non-traditional approaches that the research community is exploring for public communication and engagement; from collaboration with the arts, to digital storytelling and gaming, through to the use of comedy in locations like community spaces and festival sites.

By considering an array of different research communication opportunities, we argue that researchers may find compelling niches for both themselves and their research participants, to engage creatively alongside, or perhaps despite, increasing institutional agendas around engagement:

‘This is an era to channel creatively away from metrics or “one size fits all” and to engage in ways that work for you as an individual researcher in the context of your own disciplinary potential and desires, and that embrace and recognise the ways that people beyond the context of an organisation or university may creatively add to your research process as well as experience benefits of their own.’ (Wilkinson and Weitkamp, p.10)

We’re not suggesting in the book that all approaches to research communication need to be entirely new or novel, rather that there is a rich history of research communication which can be drawn on to develop effective, insightful and engaging approaches. Starting with a history of the field, and moving through chapters examining many tried and tested approaches, we offer the novice research communicator a set of tools and ideas via which they may build and advance their practice, often using more recent or contemporary techniques.

The book is peppered with case studies drawn from around the world; you can read up on how researchers are embedding art at CERN, using apps to allow people to experience their city in roman times via the Virtual Romans project, and supporting communities to tackle their local environmental worries through the Public Lab approach. Most chapters are supported by clear advice on practical aspects of research communication, for instance there are sections on how to utilise audience segmentation approaches, manage conflict and controversy, and principles to keep in mind when working with policymakers.

In writing the book we tried to keep a range of research areas firmly in view. As co-authors coming from two contrasting disciplines (originally working in sociology and biochemistry) we tried to consider a range of ways in which research communication can and may be relevant, and that for some researchers this may be at different points of the research journey:

‘From a research communication perspective, and particularly conversations around “impact”, there can be a tendency to focus on engagement after the fact, rather than before or during research. This neglects that whilst research has an impact on people, people also have an impact on research.’ (Wilkinson and Weitkamp, p.74)

And whilst we’ve titled the book Creative Research Communication, don’t be deceived that we see communication as only occurring in a one-directional manner. We envisage communication to include a variety of approaches, including those which embed people within research and engagement, from a participatory and dialogic perspective.

But of course impact is a very relevant issue for many research communicators at present and it can stimulate particular notions of the direction of any such impact. Recognising that, we have included a chapter on impact, which contains evaluation approaches which can be used to track the outcomes and impacts of your research communication activities on a range of participants including the researcher, as well as ways in which you might adapt evaluation to be more creative in itself. For us impact is also tied to ethical quandaries around the wider role of research communication. Is research communication about engendering change, learning, attitudes that align to our ways of thinking? Is it for all but really for some? Does research communication in and of itself need an ethical code of practice? We explore some of these themes within the book, as well as providing resources to equip researchers with techniques for ethical best practice in the design and evaluation of their research communication efforts.

In summary, we hope that the book provides a space for researchers to reflect on the ways they can engender creativity in their own research communication efforts, whilst recognising that taking such ‘risks’ requires support and encouragement:

‘Creativity can involve taking risks, having failures, pushing beyond one’s boundaries, and evaluation is one space in which to capture this, continuing to move the trajectory of research communication forwards without simply reducing research communication activities to those which might tick a box. Creative research communication is a recipe, concoction, a craft and a science, and it is up to each researcher to consider where their path lies on their own map of research communication.’ (Wilkinson and Weitkamp, p.266).

To answer our original question, do we need to be more creative in communicating research, not necessarily, but we hope the book provides a wide variety of reasons why you can.