Category Archives: Science, technology & engineering

Exploring and facilitating relationships between natural science, technology, engineering and society.

Engineering in Society – new module for engineering citizenship

Undergraduate student engineers at UWE Bristol will get the chance to learn about engineering citizenship from September.

The Science Communication Unit is launching a new module to highlight the importance of professional development, lifelong learning, and the competencies and social responsibilities required to be a professional engineer.

It follows a successful public engagement project led by Laura Fogg-Rogers in in 2014, called Children as Engineers. The new module is being funded by HEFCE to advance innovation in higher education curricula.

The 65 students, who are in the third year of their BEng or MEng degrees, will learn about the engineering recruitment shortfall and the need to widen the appeal of the profession to girls and boys. They will then develop their communication and public engagement skills in order to become STEM Ambassadors for the future.

The module is unique in that it pairs the student engineers with pre-service teachers taking BEd degrees on to be peer mentors to each other. The paired students will work together to deliver an engineering outreach activity in primary schools, as well as respectively mentoring each other in communication skills and STEM knowledge.

The children involved in the project will present their engineering designs back to the student engineers at a conference at UWE in 2018. Previous research shows that it positively changes children’s views about what engineering is and who can be an engineer .

Teacher Asima Qureshi of Meadowbrook Primary school in Bradley Stoke says;

“The Children as Engineers Project was a very successful project in our school. The highlight was the opportunity to showcase their designs at the university and be able to explain the science behind it. It has hopefully inspired children to become future engineers.”

The pilot project was also successful at improving teachers’ STEM subject knowledge confidence and self-efficacy to teach it. This is vitally important, as only 5% of primary school teachers have a higher qualification in STEM, and yet attitudes to science and engineering are formed before age 11.

Professional engineers in the Bristol region are invited to learn from the project and mentor the students as part of the new Curiosity Connections Bristol network . Delegates are welcome to attend the inaugural conference on November 23rd 2017 to share learning with other STEM Ambassadors and professional teachers in the region.

Professional engineers in the Bristol region are invited to learn from the project and mentor the students as part of the new Curiosity Connections Bristol network . Delegates are welcome to attend the inaugural conference on November 23rd 2017 to share learning with other STEM Ambassadors and professional teachers in the region.

Laura Fogg-Rogers, University of the West of England (UWE) Bristol UK

FET Award: STEM outreach at Luckwell Primary

This year, I have been lucky enough to receive a FET Award to promote STEM at a local primary school in south Bristol. Our key aims have been to use the expertise of UWE staff and students to deliver events which not only encourage children to pursue STEM careers, but also support teachers with some of the harder to achieve National Curriculum objectives.

Our first activity involved all students in Key Stage 2 – 120 in total. Inspired by the LED cards on Sparkfun, and ably assisted by fellow FARSCOPE students Hatem and Katie, we ran a lesson in which students used copper tape, LEDs and coin cell batteries to create a light-up Christmas tree or fire-side scene. Our aim was not only to show the students that electronics is fun and accessible, but to re-reinforce the KS2 National Curriculum objectives relating to electricity and conductivity.

Although a little hectic, the students really enjoyed the task and the teachers felt that the challenge of interacting with such basic components (as opposed to more “kid friendly” kits), really helped to drive home our lesson objectives.

To re-reinforce the Christmas card activity, we also ran a LED Creativity contest over the Christmas break. Students were given a pack containing some batteries, LEDs and copper tape and tasked with creating something cool.

Entries ranged from cameras with working flash to scale replicas of the school. The full range of entries and winners can be found here. Overall, we were blown away by the number and quality of the entries.

Our second focus was introducing students to programming. To this end, we have been running a regular code club every Monday, this time supported by volunteers from UWE alongside FARSCOPE student Jasper. In code club, we use a mix of materials to introduce students to the programming language scratch. We currently have 16 students attending each week and recently were lucky enough to receive a number of BBC Micro bits.

Alongside Code club, we also ran a workshop with the Year 5 class, to directly support the national curriculum objectives related to programming. Students were given Tortoise robots (Built by FARSCOPE PhD students, in honour of some of the very first autonomous robots, built in Bristol by Grey Walter). Children had to program and debug an algorithm capable of navigating a maze.

As the outreach award comes to an end, we are planning a final grand event. Each year the students at Luckwell School get to spend a week learning about real-life money matters in “Luckwell Town”. During this week, students do not attend lessons – instead, they can choose to work at a number of jobs to earn Luckwell Pounds. This year, we will be supporting Luckwell Town by helping to run a Games Development studio. Students will use Scratch to design and program simple games for other students to play in the Luckwell Arcade.

As with our prior events, the success will depend on volunteers from UWE donating their time and expertise to support us.

Luckwell Town will take place every morning of the week commencing June 12th. We are looking for volunteers to support us, so please respond to the Doodle poll if you are interested.

Martin Garrad, PhD student in robotics

Shall we talk about robots and public engagement? Ten years on.

2017 marks the ten-year anniversary since I started working on the Talking Robots project with my former SCU colleagues Karen Bultitude and Emily Dawson. A lot has been happening in robotics since then (you can read a quick summary of some key developments from the last ten years in Robotics Trends) but at the time we were interested in two key questions; What were people’s attitudes towards robotic technologies, and how were publics being engaged around these developments?

Ten years on it’s interesting to consider how many findings from this project are still relevant to public engagement. In one journal article based on this project we took the chance to explore the perspectives of the engagers and researchers involved in a series of different types of public engagement events regarding robotics in a bit more detail. The article ‘Oh yes, robots! People like Robots; the Robot people should do something’, is full of information on some of the benefits and constraints engagers identified in their work. Expectations, organisational aspects and practical issues could have a considerable impact on engagement events, but there were also signs that, a decade ago, engagers were feeling more supported and prepared to engage, and conscious of a desire amongst people to ask questions, not only to learn. We also found that definitions of public engagement, which some have more recently described as a ‘buzzword’, were by no means fixed:

‘Scientists do not operate with one definition of public engagement (Davies, 2008), instead moving between flexible, diverse and disjointed notions suggesting that ‘engagers’, ‘organisers’ and ‘audiences’ alike will change their engagement agendas if and when controversies arise.’ (Wilkinson, Bultitude and Dawson, 2010).

Alongside those seeking to engage, we were also interested in finding out a bit more about the people who participate in public engagement activities focused on robotics. In our article ‘Younger people have like more of an imagination, no offence’ we wanted to know more about why people, publics, you and me, were engaging, where they came from and what they wanted to achieve. This is something researchers are still interested in today. The recent National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine report ‘Communicating Science Effectively’ highlights that people’s ‘needs and opinions’ can change and thus, over time, effective communication must also be ‘iterative and adaptable’, perhaps no more so than in 2017.

Looking back to 2007 we found that there were lots of reasons why people were attending their local science centre, visiting a science café or participating in a school workshop. Some were attracted by the subject matter, others because it was part of their usual routines. And whilst they often empathised with the researchers they interacted with, they also had clear expectations of them and individual hopes as to what they would gain from an experience. But there were challenges:

‘Participants often struggled to identify how members of the public might participate and contribute their view in engagement settings, though often there was an underlying perception that engagement was considered ‘citizenly’. They identified that certain subjects had a greater relevance to public participation than others, in particular those with societal relevance… The challenge for those engaging publics is thus to effectively communicate the aims of such activities and appreciate the differing notions of role and participation that may exist amongst their participants.’ (Wilkinson, Dawson and Bultitude, 2012).

Some, more recent studies, continue to explore these themes, such as Gehrke’s (2014) interest in ‘existing publics’, and of course, there is now the added edge of the role of public engagement in ‘post truth politics’.

So ten years on are these issues still relevant? In my view, it’s a yes, and yes. We can still learn more about how researchers consider, engage and communicate around their work, particularly as research agendas shift and change, and the culture of engagement matures. And there’s always more to understand about people, how and why they participate, as well as why they don’t. As for robotics itself, there will also of course, be ever emerging developments, some of which will pose philosophical, ethical and social questions in the future. Are we still interested in ‘Talking Robots’, I think so.

Clare Wilkinson

Both Talking Robot articles are openly available via the UWE Research Repository:

http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/15336/8/Manuscript%20-%20Oh%20Yes%20the%20Robots.pdf

Talking Robots was funded by the ESRC (RES-000-22-2180).

New and notable – further selected publications from the Science Communication Unit

Last week we posted details of our work on environmental policy publications as well as our research on outreach and informal learning. This week’s blog highlights our work in public engagement with robotics and robot ethics, as well as our work on science communication in wider cultural areas, including film, theatre and festivals. We also revisit the controversial issue of ‘fun’ in science communication.

Robot Ethics

Winfield, A. F. (2016) Written evidence submitted to the UK Parliamentary Select Committee on Science and Technology Inquiry on Robotics and Artificial Intelligence. Discussion Paper. Science and Technology Committee (Commons), Website. Available from: http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/29428

This is a slightly unusual publication; here Professor Alan Winfield tells the story behind it. In March 2016 the UK Parliamentary Select Committee on Science and Technology opened an inquiry on Robotics and Autonomous Systems they posed four questions; the fourth of which held the greatest interest for me: The social, legal and ethical issues raised by developments in robotics and artificial intelligence technologies, and how they should be addressed? Then, in April, I was contacted by the EPSRC RAS UK network and asked if I could draft a response to this question to then form part of their response to the inquiry. This I did, but of course because of the word limit on overall responses, my contribution to the RAS UK submission was, inevitably, very abbreviated. I was also asked by Phil Nelson, CEO of EPSRC, to brief him prior to his oral evidence to the inquiry, which I was happy to do. Following the first oral evidence session I then wrote to the Nicola Blackwood MP, (then) chair of the Select Committee. In response the committee asked if they could publish my full evidence, which of course I was very happy for them to do. My full evidence was published on the committee web pages on 7 June. To compete the story the inquiry published its full report on 13 September 2016, and I was very pleased to find myself quoted in that report. I was equally pleased to see one of my recommendations – that a commission be set up – appear in the recommendations of the final report; of course other evidence made the same recommendation, but I hope my evidence helped!

Our public engagement projects also influence research as this paper by the Eurathlon consortium shows. The paper reports on the advancement of the field of robotics achieved through the Eurathlon competition:

Winfield, A. F., Franco, M. P., Brueggemann, B., Castro, A., Limon, M. C., Ferri, G., Ferreira, F., Liu, X., Petillot, Y., Roning, J., Schneider, F., Stengler, E., Sosa, D. and Viguria, A. (2016) euRathlon 2015: A multi-domain multi-robot grand challenge for search and rescue robots. In: Alboul, L., Damian, D. and Aitken, J. M., eds. (2016) Towards Autonomous Robotic Systems. (9716) Springer, pp. 351-363. Available from: http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/29283

“Fun” in science communication

The following two publications are the same text published in two different books (with permission). The chapters summarise the views of the authors, including our own Dr Erik Stengler, about the use of fun in science communication, and specifically in science centres.

Viladot, P., Stengler, E. and Fernández, G. (2016) From fun science to seductive science. In: Kiraly, A. and Tel, T., eds. (2016) Teaching Physics Innovatively 2015. ELTE University. ISBN 9789632848150 Available from: http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/27793

Viladot, P., Stengler, E. and Fernández, G. (2016) From “fun science” to seductive science. In: Franche, C., ed. (2016) Spokes Panorama 2015. ECSITE, pp. 53-65. Available from: http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/29105

Both of these are related to a rather controversial blogpost hosted on the SCU blog. That post was selected for publication in a book that captures a collection of thought-provoking blog posts from the Museum field all over the world. In it Erik expressed in a more informal and provocative manner the ideas in the above papers.

Stengler, E. (2016) Science communicators need to get it: Science isn’t fun. In: Farnell, G., ed. (2016) The Museums Blog Book. MuseumsEtc. [In Press] Available from: http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/30360

Science communication through wider cultural activities

A recent commentary explores the factors that contribute to festival goers’ choice to attend science-based events at a summer cultural festival. Presented with a huge variety of interesting cultural events, attendances at science-based events were strong, with high levels of enjoyment and engagement with scientists and other speakers. Our research found out that audiences saw science not as something distinct from “cultural” events but as just another option: Science was culture.

Sardo, A.M. and Grand, A., 2016. “Science in culture: audiences’ perspective on engaging with science at a summer festival”. Science Communication Vol. 38(2) 251–260.

This is a paper on science communication through online videos, long awaited by the small community of researchers working on this specific field who met at the conference above. It reports research conducted by interviewing the people behind the most viewed and relevant UK-based science channels in YouTube. One clear conclusion is that whilst all are aware of the great potential of online video with respect to TV broadcasting, only a few, mainly the BBC, has the insight and the means to realise it in full:

Erviti, M. d. C. and Stengler, E. (2016) Online science videos: An exploratory study with major professional content providers in the United Kingdom. Journal of Science Communication. [In Press] Available from: http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/30236

One area we are interested in is the impact of cultural events on the audience. In this recent paper, we explore the impact of a performance about haematological stem cell transplant on two key audiences: haematology nursing staff and transplant patients. The article suggests that this type of performance is beneficial to both groups, encouraging nursing staff to think differently about their patients and allowing patients to reflect on their past experience in new ways.

Weitkamp, E and Mermikides, A. (2016). Medical Performance and the ‘Inaccessible’ experience of illness: an Exploratory Study, Medical Humanities, 42:186- 193. http://mh.bmj.com/content/42/3/186 (open access)

We’re also very pleased to highlight a publication arising from a student final year project. This was first presented at an international conference in Budapest. It presents the results of a study of the Physics and Astronomy content of At-Bristol in relation to the national curriculum:

Stengler, E. and Tee, J. (2016) Inspiring pupils to study Physics and Astronomy at the science centre at-Bristol, UK. In: Kiraly, A. and Tel, T., eds. (2016) Teaching Physics Innovatively 2015. ELTE University. ISBN 9789632848150 Available from: http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/28122

As we are keen to share our learning more widely, we also occasionally report from conferences. This report, published in JCOM, summarizes highlights of the sessions Erik attended at the 15th Annual STS conference in Graz. It focuses on sessions relevant to robotics and on science communication through online videos, the latter being the session where Erik presented a paper (see next item below):

Stengler, E. (2016) 15th annual STS Conference Graz 2016. Journal of Science Communication. ISSN 1824-2049 Available from: http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/29106

We hope that you find our work interesting and insightful – details of all our publications to date can be found on the Science Communication Unit webpages.

Innovating university outreach

Corra Boushel

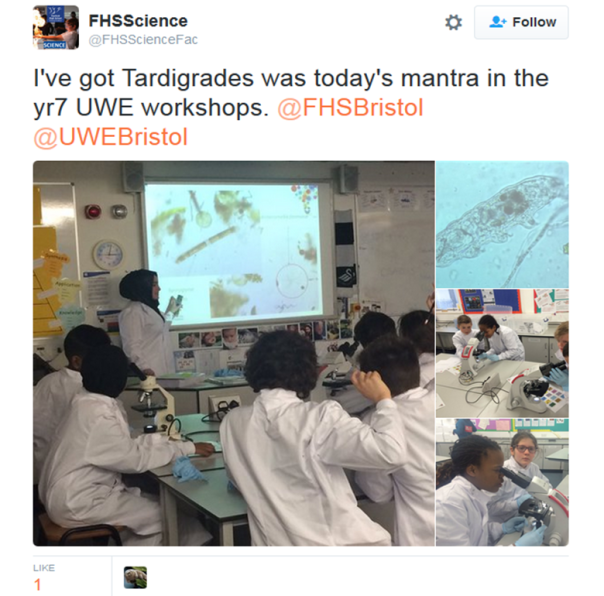

Through funding from the Higher Education Funding Council for England and internal backing, the Science Communication Unit has been involved in developing an ambitious new UWE Bristol outreach programme for secondary schools in the region. We’ve worked with over 4,000 school pupils in the last 18 months, finding tardigrades, hacking robots and solving murder mysteries with science, technology, engineering and maths.

The idea behind the project is not only to engage local communities and raise pupil aspirations. Our plan is to refocus outreach within the university so that it no longer competes with student learning or research time, but instead functions to develop undergraduate skills and to showcase UWE Bristol’s cutting edge research.

The outreach activities are developed by specialists, but then led by undergraduate students and student interns, who develop confidence and skills. UWE Bristol students can use their outreach activities to count towards their UWE Futures Award, and in some degree courses we are looking at ways that outreach projects can provide credit and supplement degree modules. Researchers can use the activities to increase their research impact and share their work with internal and external audiences – getting students excited about research through explaining it to young people. Enabling students to lead outreach – including Science Communication Masters and Postgraduate Certificate students – means that the university delivers more activities, reaching more schools and giving more school pupils the chance to participate.

The brainchild of UWE Bristol staff Mandy Bancroft and John Lanham, the development stages of the project have been led by Debbie Lewis and Corra Boushel from the Faculty for Health and Applied Science and the Science Communication Unit with support from Laura Fogg Rogers. The project is now being expanded into a university-wide strategy with cross-faculty support to cover all subject areas, not only STEM.

Special thanks on the project go to all of our student ambassadors and previous interns, as well as our current team of Katherine Bourne, Jack Bevan and Tay-Yibah Aziz. Katherine and Tay-Yibah are employed on the project alongside their studies in the Science Communication Unit.

Special thanks on the project go to all of our student ambassadors and previous interns, as well as our current team of Katherine Bourne, Jack Bevan and Tay-Yibah Aziz. Katherine and Tay-Yibah are employed on the project alongside their studies in the Science Communication Unit.

An Ethical Roboticist: the journey so far

What do robots have to do with ethics? And how do you end up with the job of “roboethicist”? Prof. Alan Winfield, Director of the Science Communication Unit at UWE Bristol, explains his recent professional journey.

It was November 2009 that I was invited, together with Noel Sharkey, to present to the EPSRC Societal Impact Panel on robot ethics. That was I think my first serious foray into robot ethics. An outcome of that meeting was being asked to co-organise a joint AHRC/EPSRC workshop on robot ethics – which culminated in the publication of the Principles of Robotics in 2011: on the EPSRC website, and with a writeup in New Scientist.

Shortly after that I was invited to join a UK robot ethics working group which then became part of the British Standards Institute technical committee working toward a Standard on Robot Ethics. That standard was published earlier this month, as BS 8611:2016 Guide to the ethical design and application of robots and robotic systems. Sadly the standard itself is behind a paywall, but the BSI press release gives a nice writeup. I think this is probably the world’s first standard for robot ethics and I’m very happy to have contributed to it.

Somehow during all of this I got described as a roboethicist; a job description I’m very happy with.

In parallel with this work and advocacy on robot ethics, I started to work on ethical robots; the other side of the roboethics coin. But, as I wrote in PC-PRO last year it took a little persuasion from a long term collaborator, Michael Fisher, that ethical robots were even possible. But since then we have experimentally demonstrated a minimally ethical robot; work that was covered in New Scientist, the BBC R4 Today programme and last year a Nature news article. I was especially pleased to be invited to present this work at the World Economic Forum, Davos, in January. Below is the YouTube video of my 5 minute IdeasLab talk, and a writeup.

To bring the story right up to date, the IEEE initiated an international initiative on Ethical Considerations in the Design of Autonomous Systems, and I am honoured to be co-chairing the General Principles committee, as well as sitting on the How to Imbue Ethics into AI committee. The significance of this is that the IEEE effort will be covering all intelligent technologies including robots and AI. I’ve become very concerned that AI is moving ahead very fast – much faster than robotics – and the need for ethical standards and ultimately regulation is even more urgent than in robotics.

It’s very good also to see that the UK government is taking these developments seriously. I was invited to a Government Office of Science round table in January on AI, and just last week submitted text to the parliamentary Science and Technology committee inquiry on Robotics and AI.

You can find out more about Alan’s research and engagement on his own blog.

The story behind the cameras: filming robots

In 2013, just as I was finishing my Masters in Science Communication at UWE Bristol, I was asked to help film the euRathlon robotics competition in Germany. euRathlon was inspired by the situation that officials were faced with after the nuclear accident in Fukushima in 2011. The competition challenges robotics engineers to solve the problems of dealing with an emergency scenario, pushing innovation and creativity in the robotics domain. The project is led by Prof. Alan Winfield from UWE alongside seven other partner institutions. The 2015 euRathlon competition in Piombino, Italy combined land, sea and air challenges for the robots to overcome. Our 2015 film team included three of us (Josh Hayes Davidson on graphics, Charlie Nevett on camera and myself – Tim Moxon – as producer and sound engineer), taking with us all the lessons I learned from 2013.

Filming robots, particularly complex robots designed to respond to emergency scenarios, is a daunting task. Trying to make sure that we didn’t get too technical was always going to be a problem. We had the additional issue that English was not the first language of most of the people being interviewed which really added to the challenge. Taking care and with plenty of re-shoots we managed to get round both of the problems by sticking to the golden rules: take it slow and keep it simple. This made sure that we never lost sight of what we were trying to do. Our focus was always to bring 21st century robotics into the public eye.

The first two days of the competition presented the individual land, sea and air trials. On site we first created two “meet the teams” films where we interviewed all 16 teams and got to know them. Luckily they were all super friendly and very cooperative which meant we got all the teams interviewed in two days. After that the real work began. The land trials were easy enough to film and get a good story line of shots as the robots were almost always visible. However the underwater robots required a bit more imagination. In the end a GoPro on a piece of drift wood got us the shots we needed.

The aerial robots had some issues too as getting long distance shots was not always easy. Fortunately Josh and Charlie were more than up to the task.

Day 3 and 4 focused on combining two domains, so land and sea or air and land etc. Day 3 went well with fantastic interviews with judges and teams helping to really give some depth to the videos. Again underwater proved to be a bit challenging but we managed, with the help of some footage given to us by the teams that they took on-board their robots. Day 4 didn’t go as well as the second half of the competition had to be cancelled due to strong winds. Wind had been an issue throughout the competition and all of our equipment required regular cleaning to keep the dust out, as well as dealing with constant wind when recording sound.

That day however you could barely stand in the open for all the dust and sand being kicked up by the wind and getting good sound for interviews was nearly impossible. We could only hope that the weather improved for the Grand Challenge.

The final days were the Grand Challenge, as much for us filming as for those competing. The timescale was starting to tighten as we only had two days to film, cut and polish the remaining two videos. With increasing pressure to produce high quality products we pulled out all the stops. Fortunately all the teams rose to the occasion and provided us with some spectacular on-board footage as well as some nice underwater diver footage. The Grand Challenge turned out to be a great success with all the teams at least competing even if they didn’t all finish the challenge.

Tim Moxon completed the UWE Bristol Masters in Science Communication in 2013.

For more information about EuRathlon please visit the project website.

What I learnt working with robots, children and animals

Put two robotics researchers in a small room with a bad tempered snake, 30 children and a zoologist. And make sure everyone learns something and enjoys themselves.

That was the goal of a recent SCU-led project called ‘Robots vs Animals,’ a collaboration with Bristol Zoo Gardens education unit and Bristol Robotics Laboratory, with funding from the Royal Academy of Engineering. I’ll admit that was not how the project was originally defined, but it was the situation I found myself in as project coordinator last March.

The snake was a grumpy Columbian rainbow boa called Indigo, who was supposed to be demonstrating energy efficiency in the animal kingdom. The researchers were specialists on Microbial Fuel Cells, a system that can convert organic matter into electricity. They work on highly innovative designs that get power from urine – but only a small amount at a time, hence the need for energy efficiency. The kids were 12 and 13 year olds from a local school who were learning about biomimicry and seeing the cutting edge applications of science and maths. In this project I think I learnt as much about public engagement as they did about robots.

- Make contact.

I mean human, skin contact. It’s an old chestnut of engagement, but it proved itself once again. Even when bits of equipment broke – or were broken before we even started – the audiences really appreciated getting to hold and touch things themselves. This applied as much to the wires, switches and circuit boards of the robots as the cuddly and creepy animals. A ‘robot autopsy’ (bits and bobs from the scrap bin at the Lab) went down a storm in a Bristol primary school and a Pint of Science pub quiz. Watching school students handle a Nao robot as carefully as a baby was a project highlight for me and featured strongly in their positive feedback.

I mean human, skin contact. It’s an old chestnut of engagement, but it proved itself once again. Even when bits of equipment broke – or were broken before we even started – the audiences really appreciated getting to hold and touch things themselves. This applied as much to the wires, switches and circuit boards of the robots as the cuddly and creepy animals. A ‘robot autopsy’ (bits and bobs from the scrap bin at the Lab) went down a storm in a Bristol primary school and a Pint of Science pub quiz. Watching school students handle a Nao robot as carefully as a baby was a project highlight for me and featured strongly in their positive feedback.

- Keep contact.

I was physically based in the Bristol Robotics Laboratory for the duration of the project, and it made a huge difference being around the researchers outside of our meetings and in between emails. I could get a much better sense of their projects, interests and personalities by seeing them every week, even if I theoretically could have coordinated the project from the SCU offices on the other side of the campus. Being around also helped to give the project a higher profile inside a busy, hard-working research lab where time for public engagement is limited.

- Have contacts.

The project evolved from its main focus of classes at Bristol Zoo Gardens to include a short film with a local science centre, talks and stalls at public events and even a teacher training seminar. Being able to say ‘yes’ to opportunities as they arose from different quarters is a luxury that not all projects can afford, but I found it was important to stay open to opportunities as the project developed. Attention to how the project outputs are worded in the first place helps, so does listening carefully to the needs of participants and interested parties and having a great project manager (thanks Laura Fogg Rogers!).

So how did all of that help with an irascible snake, excitable kids and nervous researchers? Firstly, Zoo staff quickly went to find a snake that would be more amenable to being stroked, to allow for first contact. I attended the session alongside the researchers even though they were leading it. This meant I could give feedback and support, and had the honour of watching as they became more skilled and relaxed. Having seen how they kept their nerve with the uncivil serpent, I knew I could rely on those researchers to handle other difficult situations – like appearing in front of a camera when the opportunity arose. Finally, when we had the chance to showcase their research at another event, we made use of our contacts and took the docile cockroaches with us rather than Indigo the snake.

Corra Boushel is a project coordinator in the Science Communication Unit. Robots vs Animals was supported by the Royal Academy of Engineering Ingenious Awards. Thanks to the Science Communication Unit and Bristol Robotics Laboratory at the University of the West of England and Bristol Zoo Gardens.

No snakes were harmed during this project.