Blog Archives

New and notable – further selected publications from the Science Communication Unit

Last week we posted details of our work on environmental policy publications as well as our research on outreach and informal learning. This week’s blog highlights our work in public engagement with robotics and robot ethics, as well as our work on science communication in wider cultural areas, including film, theatre and festivals. We also revisit the controversial issue of ‘fun’ in science communication.

Robot Ethics

Winfield, A. F. (2016) Written evidence submitted to the UK Parliamentary Select Committee on Science and Technology Inquiry on Robotics and Artificial Intelligence. Discussion Paper. Science and Technology Committee (Commons), Website. Available from: http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/29428

This is a slightly unusual publication; here Professor Alan Winfield tells the story behind it. In March 2016 the UK Parliamentary Select Committee on Science and Technology opened an inquiry on Robotics and Autonomous Systems they posed four questions; the fourth of which held the greatest interest for me: The social, legal and ethical issues raised by developments in robotics and artificial intelligence technologies, and how they should be addressed? Then, in April, I was contacted by the EPSRC RAS UK network and asked if I could draft a response to this question to then form part of their response to the inquiry. This I did, but of course because of the word limit on overall responses, my contribution to the RAS UK submission was, inevitably, very abbreviated. I was also asked by Phil Nelson, CEO of EPSRC, to brief him prior to his oral evidence to the inquiry, which I was happy to do. Following the first oral evidence session I then wrote to the Nicola Blackwood MP, (then) chair of the Select Committee. In response the committee asked if they could publish my full evidence, which of course I was very happy for them to do. My full evidence was published on the committee web pages on 7 June. To compete the story the inquiry published its full report on 13 September 2016, and I was very pleased to find myself quoted in that report. I was equally pleased to see one of my recommendations – that a commission be set up – appear in the recommendations of the final report; of course other evidence made the same recommendation, but I hope my evidence helped!

Our public engagement projects also influence research as this paper by the Eurathlon consortium shows. The paper reports on the advancement of the field of robotics achieved through the Eurathlon competition:

Winfield, A. F., Franco, M. P., Brueggemann, B., Castro, A., Limon, M. C., Ferri, G., Ferreira, F., Liu, X., Petillot, Y., Roning, J., Schneider, F., Stengler, E., Sosa, D. and Viguria, A. (2016) euRathlon 2015: A multi-domain multi-robot grand challenge for search and rescue robots. In: Alboul, L., Damian, D. and Aitken, J. M., eds. (2016) Towards Autonomous Robotic Systems. (9716) Springer, pp. 351-363. Available from: http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/29283

“Fun” in science communication

The following two publications are the same text published in two different books (with permission). The chapters summarise the views of the authors, including our own Dr Erik Stengler, about the use of fun in science communication, and specifically in science centres.

Viladot, P., Stengler, E. and Fernández, G. (2016) From fun science to seductive science. In: Kiraly, A. and Tel, T., eds. (2016) Teaching Physics Innovatively 2015. ELTE University. ISBN 9789632848150 Available from: http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/27793

Viladot, P., Stengler, E. and Fernández, G. (2016) From “fun science” to seductive science. In: Franche, C., ed. (2016) Spokes Panorama 2015. ECSITE, pp. 53-65. Available from: http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/29105

Both of these are related to a rather controversial blogpost hosted on the SCU blog. That post was selected for publication in a book that captures a collection of thought-provoking blog posts from the Museum field all over the world. In it Erik expressed in a more informal and provocative manner the ideas in the above papers.

Stengler, E. (2016) Science communicators need to get it: Science isn’t fun. In: Farnell, G., ed. (2016) The Museums Blog Book. MuseumsEtc. [In Press] Available from: http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/30360

Science communication through wider cultural activities

A recent commentary explores the factors that contribute to festival goers’ choice to attend science-based events at a summer cultural festival. Presented with a huge variety of interesting cultural events, attendances at science-based events were strong, with high levels of enjoyment and engagement with scientists and other speakers. Our research found out that audiences saw science not as something distinct from “cultural” events but as just another option: Science was culture.

Sardo, A.M. and Grand, A., 2016. “Science in culture: audiences’ perspective on engaging with science at a summer festival”. Science Communication Vol. 38(2) 251–260.

This is a paper on science communication through online videos, long awaited by the small community of researchers working on this specific field who met at the conference above. It reports research conducted by interviewing the people behind the most viewed and relevant UK-based science channels in YouTube. One clear conclusion is that whilst all are aware of the great potential of online video with respect to TV broadcasting, only a few, mainly the BBC, has the insight and the means to realise it in full:

Erviti, M. d. C. and Stengler, E. (2016) Online science videos: An exploratory study with major professional content providers in the United Kingdom. Journal of Science Communication. [In Press] Available from: http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/30236

One area we are interested in is the impact of cultural events on the audience. In this recent paper, we explore the impact of a performance about haematological stem cell transplant on two key audiences: haematology nursing staff and transplant patients. The article suggests that this type of performance is beneficial to both groups, encouraging nursing staff to think differently about their patients and allowing patients to reflect on their past experience in new ways.

Weitkamp, E and Mermikides, A. (2016). Medical Performance and the ‘Inaccessible’ experience of illness: an Exploratory Study, Medical Humanities, 42:186- 193. http://mh.bmj.com/content/42/3/186 (open access)

We’re also very pleased to highlight a publication arising from a student final year project. This was first presented at an international conference in Budapest. It presents the results of a study of the Physics and Astronomy content of At-Bristol in relation to the national curriculum:

Stengler, E. and Tee, J. (2016) Inspiring pupils to study Physics and Astronomy at the science centre at-Bristol, UK. In: Kiraly, A. and Tel, T., eds. (2016) Teaching Physics Innovatively 2015. ELTE University. ISBN 9789632848150 Available from: http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/28122

As we are keen to share our learning more widely, we also occasionally report from conferences. This report, published in JCOM, summarizes highlights of the sessions Erik attended at the 15th Annual STS conference in Graz. It focuses on sessions relevant to robotics and on science communication through online videos, the latter being the session where Erik presented a paper (see next item below):

Stengler, E. (2016) 15th annual STS Conference Graz 2016. Journal of Science Communication. ISSN 1824-2049 Available from: http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/29106

We hope that you find our work interesting and insightful – details of all our publications to date can be found on the Science Communication Unit webpages.

Postgraduate Science Communication students get stuck in on ‘Science in Public Spaces’

Emma Weitkamp & Erik Stengler

September saw the lecturing staff at the Science Communication Unit welcoming our new MSc Science Communication and PgCert Practical Science Communication students to UWE and Bristol. It also sees the start of our refreshed programme offering, which includes significant changes and updates to two of our optional modules: Science in Public Spaces and Science on Air and On Screen.

The first three-day block of Science in Public Spaces (SiPS) marks the start of a diverse syllabus that seeks to draw together themes around face-to-face communication, whether that takes place in a what we might think of as traditional science communication spaces: museums, science centres and festivals or less conventional spaces, such as science comedy, theatre or guided trails. Teaching is pretty intense, so from Thursday, 29th September to Saturday, 1st October, students got stuck into topics ranging from the role of experiments and gadgets to inclusion and diversity.

Practical science fair

Thursday, 29th September saw the 13 SiPS students matched with researchers from the Faculty of Health and Applied Sciences. Students were introduced to cutting edge research and have been challenged to think about how this could be communicated to the public in a science fair setting. Each student will work with their researcher to create a hands-on activity which they will have the opportunity to deliver to the public at a science fair to be held during a University Open Day in the spring.

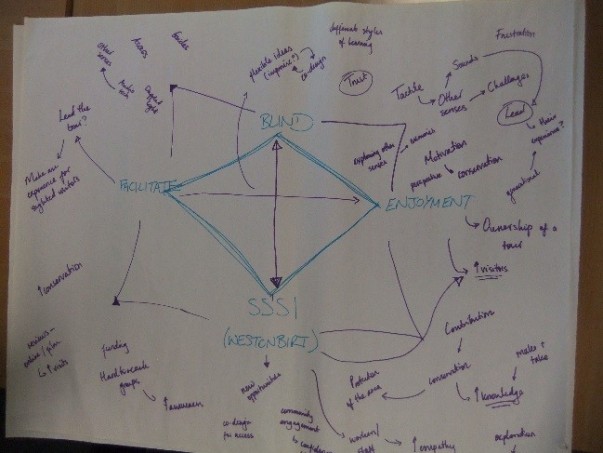

Towards the end of the three days a session on creativity generated intense discussion about how we might judge what creativity is through to practical techniques and tips we might use to stimulate creative thinking. The session included a word diamond (McFadzean, 2000), where groups considered how you might foster engagement and enjoyment amongst blind visitors to the Grand Canyon, how blind visitors could be involved in creating a sensory trail (for sighted people) at an arboretum or how to enable a local community to be involved in decision making around land use that involved ecosystem services trade-offs. Challenging topics that draw on learning from earlier in the week.

After a final session on connecting with audiences, students (and staff) were looking a little tired; three days of lectures, seminars and workshops is exhausting. We hope students left feeling challenged, excited and ready to start exploring this new world of science communication and public engagement and that they find ways to connect their studies with events and activities they enjoy in their leisure time – though that might not apply to the seminar reading!

Science in Public Spaces got off to an excellent start, thanks to the students for their engaged and thoughtful contributions in class. Up next is the Writing Science module, where Andy Ridgway, Emma Weitkamp and a host of visiting specialists will be introducing students to a wide range of journalistic techniques and theories. Then it will be the turn of the new Science on Air and on Screen where Malcolm Love will introduce students to techniques for broadcasting science whether on radio, TV or through the range of digital platforms now open to science communicators. Looks to be an exciting year!

McFadzean, E. (2000) Techniques to enhance creativity. Team Performance Management: An International Journal, 6 (3/4) pp. 62 – 72

Tackling the challenge of engaging with drought and frogs

SCU was well represented at the Bristol Festival of Nature (BFON) in June, with Associate Professor Emma Weitkamp manning the Drought Risk and You (DRY) stand on Saturday and MSc student Hannah Conduit showcasing her research with the Durrell Trust as part of UWE’s festival tent.

Emma is exploring communication and engagement barriers and enablers related to drought and water scarcity within the DRY project. At BFON, Emma was interested to hear what visitors think about a set of cartoons produced as part of the project and whether these might be a tool to open conversations about water scarcity; climate change models suggest the UK will have wetter winters and drier summers, increasing the risk that we will have serious droughts. . In the southern UK, the most severe in living memory is the drought of ’76.

Emma is exploring communication and engagement barriers and enablers related to drought and water scarcity within the DRY project. At BFON, Emma was interested to hear what visitors think about a set of cartoons produced as part of the project and whether these might be a tool to open conversations about water scarcity; climate change models suggest the UK will have wetter winters and drier summers, increasing the risk that we will have serious droughts. . In the southern UK, the most severe in living memory is the drought of ’76.

Initial work within the DRY project highlights the challenges of engaging people with Drought. Unlike flooding which has immediate effects, drought has a slow onset and many not have immediate relevance to many people. Rain during BFON highlights the challenge – how do you engage people with drought when it’s raining?

Emma Weitkamp and DRY Project leader Lindsey McEwen at the DRY stand, Bristol Festival of Nature

Emma presented initial work on citizen science aspects of the DRY project at the Society for Risk Analysis meeting in Bath, 20th June, while Adam Corner, of Climate Outreach presented the project’s initial work on communication barriers.

Jeff Dawson with the project research tools

Frogs are not the cuddliest of species, so Hannah is tackling similar challenges through her research with the Durrell Trust. Amphibians have suffered a dramatic decline in numbers, and around 40% of all amphibian species are now considered to be under threat. But in a world of glamorous tigers and cuddly lemurs, it is sometimes hard for frogs to get a look in.

Hannah’s research focuses on one particular species of frog; second largest in the world and perhaps one of the most endangered. The ‘Mountain Chicken’ is aptly named for its meat; prised locally as a delicacy with taste and consistency similar to that of its feathery cousin.

With less than 100 individuals remaining in the wild and continued threat from disease, the Durrell Trust and UWE are working together to find more effective ways of communicating the plight of amphibians like the Mountain Chicken.

At BFON, Hannah and her Durrell supervisor, Jeff, along with a small group of volunteers talked with the public about the Mountain Chicken’s story, as well as showing them some of the methods used by scientists and researchers to monitor the remaining wild frogs. Scanning the stall’s microchipped frog plushies and swabbing them for a fungal disease called Chytrid proved to be the weekend’s most popular activities.

Erik Stengler, Hannah Conduit and Jeff Dawson, at the Saving the Mountain Chicken Frog stand, Bristol Festival of Nature

Research is currently ongoing for Hannah’s project, and will culminate in a handbook for use by the Mountain Chicken Recovery Programme in raising awareness and gathering interest amongst the public for the species.

Blog post written by Emma Weitkamp & Hannah Conduit

MSc Broadcasting Science students in action!

As part of our MSc in Science Communication students have the option to choose a Broadcasting Science module (‘Science on Air and On Screen’ for 2016/17 onwards). The module enables students to build their radio, TV and digital media skills by critically exploring the role of broadcast media in the communication of science. Students make an ‘as live’ radio magazine programme about science, and a short film. On many occasions these films were selected to be shown on the Big Screen on Millennium Square, Bristol, during the Festival of Nature.

The module is taught by Erik Stengler , Senior Lecturer in Science Communication and Malcolm Love , Associate Lecturer in Science Communication, and includes the use of facilities at the BBC Bristol and the production company Films@59.

You can watch the impressive short films made by our recent MSc students below.

2013

2014

2015

2016

The Science Communication Unit at UWE Bristol is renowned for its innovative and diverse range of national and international activities designed to engage the public with science. Our MSc Science Communication course is an excellent opportunity to benefit from the Unit’s expertise, resources and contacts.

As well as drawing on the academic and practical experience of staff within the Science Communication Unit, our programme gives students an opportunity to meet a range of visiting lecturers and benefit from their practical experience. This also provides an excellent networking opportunity for students interested in developing contacts among science communication practitioners. The course combines a solid theoretical background with practical skill development, and has excellent links with the sectors and industries it informs.

If you are interested in finding out more about our Science Communication Masters or Postgraduate Certificate, please visit our website.

Science communicators need to get it: science isn’t fun.

I am writing on the flight that takes me to a conference in Warsaw, which will nicely draw to a close a research cycle that started shortly after I joined the SCU. As part of my job interview at UWE Bristol almost exactly 4 years ago, I said that one of the things I hoped to share was concerns about the role of “fun” in science communication, and specifically in science centres. These concerns had developed during the decade or so I had spent working in science centres and with the media and I felt they needed to be addressed through academic research alongside practitioners.

I am unable to tell exactly when and where I developed an interest in investigating this currently ubiquitous trend of “fun,” but I found I was not alone in this endeavour. I liaised and collaborated with Guillermo Fernández, an engineer and exhibit designer I knew from the times when he would offer his services to the science centre I worked at. We were later joined by Pere Viladot, a very experienced museum educator and since recently PhD in science education. I was also able to draw into the investigation various undergraduate students in their final year at UWE, through their third year project. I must say, as well as ticking the boxes of integrating research into teaching and providing a unique student experience (in that the students did real original research, as opposed to repeat experiments of well-known phenomena), this has been the part that I enjoyed most. It was simply awesome to see these undergraduates doing research work that was often of better quality than what we see in MSc dissertations, and to share their excitement at seeing their work being accepted and presented at international conferences.

Scientists see their work as fascinating, intriguing, exciting, interesting or important, but not “fun.”

So, quite early on, student Megan Lyons explored the perception of the “fun” in science by people at different stages of their scientific career, showing that with time and experience “fun” becomes less and less of an adjective used to describe their work, and that there are many other words that are preferred in its stead, such as “fascinating, intriguing, exciting, interesting, or important”, to name but a few. We presented this at a conference in Lodz (Poland), where people involved in Childrens’ Universities met to discuss their practice. It was quite an eye opener to encounter such a lack of understanding of what I was saying, and in the lively Q&A session I kept having to repeat again and again what we were warning against (conveying the message that science is fun) and what we weren’t (making science teaching and communication as fun as possible).

In the context of science centres, undergraduate student Hannah Owen had already explored whether science centres are actually addressing and providing opportunities for “dialogue” between science and society. Her analysis of At-Bristol and Techniquest that concluded that indeed they are not, and that the only attempts to do so are through activities and events, not through the exhibitions. This was presented at the 2013 edition of the Science in Public Conference in Nottingham and recently selected for publication in the Pantaneto Forum.

Science centres have tried and failed to understand their own role… and it sends out the wrong message about science.

This provided another example in which to understand how science centres have tried and failed to find a way to understand their own role, focusing on “fun” being just one more of these attempts. Reflecting on this we have been able to identify various “wrong messages” that are conveyed in this way: it sends out the wrong message about science communication (deterring scientists from engaging in it), about science (as being a scientist is definitely not about having fun), about science education (as it seems one has to go out of the classroom to have fun, the conclusion being that class is boring), about science centres (as they become a venue of entertainment only, displacing from them valuable approaches such as inquiry based learning, for which they are an ideal venue), and about children (as it condescendingly assumes they would only engage in things that are fun).

We presented these reflections at the EASST 2014 conference in Torun (Poland) and to Physics teachers at the TPI-2015 (Teaching Physics Innovatively) conference in Budapest, where undergraduate student Jessica Tee complemented the research with the outcomes of her final year project. She confirmed that science centres are indeed a valuable educational resource, thus reinforcing the message that this is not something they should lose at the expense of concentrating on providing “fun”.

Science centres need to return to the long forgotten principles of museology, which is the language they speak and master.

Now in Poland I will present all this to the science centre community, which were the only players of the field to which we had not yet had the occasion to communicate our proposal. We think that instead of “fun,” science centres should focus on what they do best and constitutes their core business, namely exhibitions. To do so, they need to return to the long forgotten principles of museology, which is the language they speak and master, just as movies use the cinematographic language. This means that museologists need to be engaged, something that does not currently happen. In the educational front, science centres could use such well-designed and conceived exhibitions as the “field” for data collection in inquiry based learning. Again, to do so they need a shift in their hiring: this needs highly qualified educators instead of – or at least in addition to – museum explainers that are volunteers, interns or other temporary staff. The alterative is science centres trying to compete with other venues or options in what these others do best (fun, entertainment, multimedia & audiovisual communication etc…), hardly a promising prospect in the long run.

Just two days ago we submitted an article about this to Ecsite’s SPOKES magazine, and another one in more detail is about to appear in the Spanish Journal of Museology. Together with the presentation in Warsaw they constitute a satisfactory culmination of this collaboration. As the plane prepares to land (and I am asked to switch of this tablet), I can’t help enjoying a sense of achievement and starting to look forward to the next research cycle on which I will report in due course…

Erik Stengler is a Senior Lecturer in Science Communication at UWE.

@eriks7