Blog Archives

Communicating science across Europe

Since May 2016, the Science Communication Unit has been involved with a four year, Europe-wide research project ClairCity. Laura Fogg Rogers, Margarida Sardo and Corra Boushel are all staff members on the project, leading the communication, dissemination and evaluation. Working on large-scale international projects requires a slightly different set of sci-comm skills to local or national projects. ClairCity is specifically about air pollution in cities, so communication is also affected by the fact that the team are working on issues that affect the public and their health every day.

Since May 2016, the Science Communication Unit has been involved with a four year, Europe-wide research project ClairCity. Laura Fogg Rogers, Margarida Sardo and Corra Boushel are all staff members on the project, leading the communication, dissemination and evaluation. Working on large-scale international projects requires a slightly different set of sci-comm skills to local or national projects. ClairCity is specifically about air pollution in cities, so communication is also affected by the fact that the team are working on issues that affect the public and their health every day.

ClairCity is an innovative air quality project involving citizens and local authorities in six countries around Europe. There are sixteen partner organisations involved in the project, which is funded by the EU Horizon 2020 fund. The project activities are geographically focused in six areas – two regions and four cities. These are: Amsterdam in the Netherlands; Bristol in the UK; Ljubljana in Slovenia; Sosnowiec in Poland; the Aveiro region in Portugal and the Liguria region around Genoa in Italy. The project aims to model citizens’ behaviour and activities to enrich public engagement with city, national and EU policy making about air quality and health. The resulting policy scenarios will allow cities to work towards improved air quality, reduced carbon emissions, improved public health outcomes and greater citizen awareness.

Each city or region is hosting a series of events and special activities to engage citizens in the ClairCity process and with the issues of air pollution and public health. The range of activities is designed to attract a range of different audiences into the project. There are large, online surveys, face-to-face encounters, workshops for citizens and local organisations, an online game, a free app, a schools’ competition, film-making with older people, city events and celebrations of cleaner air and better health. Promoting each of these requires planning for different audiences, meaning different media of communication, messaging, timescales and targets.

Our public activities in Bristol will start in May 2017, with our Bristol game release scheduled for April 2018.

Top tips for large, international projects:

- Get to know your partners. They are the gatekeepers to your local audiences and they will know the issues, processes and politics.

- Translation is an art, not a science. Google translate can do marvels to understand incoming emails or tweets, but of course if you are communicating with a public outside of the writer’s native language, find a translator that you trust. This might even need to be a science writer.

- Art can be international. Strong graphics can help to give your project a shared identity across multiple languages, in a way that infographics, diagrams and text will struggle. ClairCity had a graphic notetaker at the first project meeting and the output has been invaluable to giving an identity to the project.

- Don’t forget time differences when organising skype calls!

Dr. Corra Boushel

Innovating university outreach

Corra Boushel

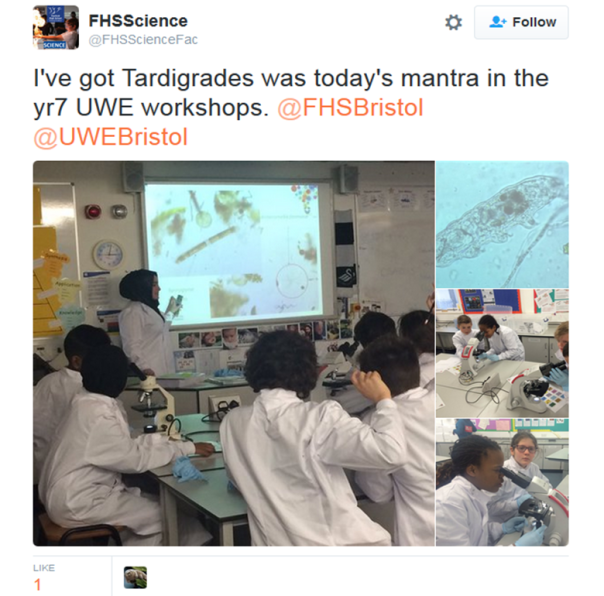

Through funding from the Higher Education Funding Council for England and internal backing, the Science Communication Unit has been involved in developing an ambitious new UWE Bristol outreach programme for secondary schools in the region. We’ve worked with over 4,000 school pupils in the last 18 months, finding tardigrades, hacking robots and solving murder mysteries with science, technology, engineering and maths.

The idea behind the project is not only to engage local communities and raise pupil aspirations. Our plan is to refocus outreach within the university so that it no longer competes with student learning or research time, but instead functions to develop undergraduate skills and to showcase UWE Bristol’s cutting edge research.

The outreach activities are developed by specialists, but then led by undergraduate students and student interns, who develop confidence and skills. UWE Bristol students can use their outreach activities to count towards their UWE Futures Award, and in some degree courses we are looking at ways that outreach projects can provide credit and supplement degree modules. Researchers can use the activities to increase their research impact and share their work with internal and external audiences – getting students excited about research through explaining it to young people. Enabling students to lead outreach – including Science Communication Masters and Postgraduate Certificate students – means that the university delivers more activities, reaching more schools and giving more school pupils the chance to participate.

The brainchild of UWE Bristol staff Mandy Bancroft and John Lanham, the development stages of the project have been led by Debbie Lewis and Corra Boushel from the Faculty for Health and Applied Science and the Science Communication Unit with support from Laura Fogg Rogers. The project is now being expanded into a university-wide strategy with cross-faculty support to cover all subject areas, not only STEM.

Special thanks on the project go to all of our student ambassadors and previous interns, as well as our current team of Katherine Bourne, Jack Bevan and Tay-Yibah Aziz. Katherine and Tay-Yibah are employed on the project alongside their studies in the Science Communication Unit.

Special thanks on the project go to all of our student ambassadors and previous interns, as well as our current team of Katherine Bourne, Jack Bevan and Tay-Yibah Aziz. Katherine and Tay-Yibah are employed on the project alongside their studies in the Science Communication Unit.

It’s 2016: Are we communicating effectively?

Corra Boushel is a project coordinator at the SCU.

A recent experience with an organisation I won’t name left me disappointed, annoyed and then worried. Something I took for granted as straightforward turned out to be impossible for the other organisation to incorporate. It set me thinking: are the institutions I’ve worked at so unique? What is typical in similar organisations – universities, research centres, industry institutes etc – and what’s the norm in science-communication-land? It has repercussions for coordination between organisations, but also important ones for the environment. It reflects badly on our institutions and us individually if we fail to meet others’ expectations. In a nutshell: in 2016 am I wrong to expect we can all use Skype*?

Now when I say “we” I’m not assuming that absolutely everyone in the world has internet, or the know-how or desire to get themselves online. My dad will only skype if my mum sets it up and sits next to him, and that’s ok by him. I have worked at organisations with offices in developing countries where intermittent power supplies, crummy internet and occasional natural disasters hijacked our attempts to connect on a regular basis. But here I’m talking about professionally – between scientific, research and industry institutions – in the UK. I thought everyone did this nowadays but after my recent experience, was I wrong?

What are our technological (and environmental) standards as an industry?

I know there are plenty of situations where online calls are less satisfying or appropriate than face-to-face meetings. I sit next to researchers who are looking at the importance of gesturing in human interaction, and how robots and computer systems can’t (yet) mimic that. I think it helps enormously at the start of new projects if you can get around a table and see eye-to-eye. Large group dynamics do not translate well down ethernet cables. There are many reasons why Skype might be a lesser alternative, but to me it is also an invaluable option. Furthermore, within science communication we see online communication being used to great effect: projects like ‘I’m A Scientist Get Me Out Of Here’ just wouldn’t grab the attention of young people in the same way if the class had to all write letters; here at UWE we offer online science communication courses so that people all across the world can participate.

I’m curious to find out: What does your office or institution provide? Should video conferencing be an option – I’m not saying a requirement – as a minimum standard to save travel time, money and emissions? What are our technological (and environmental) standards as an industry? I’d be interested to hear your thoughts and experiences below – or you can email me directly corra.boushel-at-uwe.ac.uk if you’d like your comments posted anonymously.

*Other online communication software is available.

What I learnt working with robots, children and animals

Put two robotics researchers in a small room with a bad tempered snake, 30 children and a zoologist. And make sure everyone learns something and enjoys themselves.

That was the goal of a recent SCU-led project called ‘Robots vs Animals,’ a collaboration with Bristol Zoo Gardens education unit and Bristol Robotics Laboratory, with funding from the Royal Academy of Engineering. I’ll admit that was not how the project was originally defined, but it was the situation I found myself in as project coordinator last March.

The snake was a grumpy Columbian rainbow boa called Indigo, who was supposed to be demonstrating energy efficiency in the animal kingdom. The researchers were specialists on Microbial Fuel Cells, a system that can convert organic matter into electricity. They work on highly innovative designs that get power from urine – but only a small amount at a time, hence the need for energy efficiency. The kids were 12 and 13 year olds from a local school who were learning about biomimicry and seeing the cutting edge applications of science and maths. In this project I think I learnt as much about public engagement as they did about robots.

- Make contact.

I mean human, skin contact. It’s an old chestnut of engagement, but it proved itself once again. Even when bits of equipment broke – or were broken before we even started – the audiences really appreciated getting to hold and touch things themselves. This applied as much to the wires, switches and circuit boards of the robots as the cuddly and creepy animals. A ‘robot autopsy’ (bits and bobs from the scrap bin at the Lab) went down a storm in a Bristol primary school and a Pint of Science pub quiz. Watching school students handle a Nao robot as carefully as a baby was a project highlight for me and featured strongly in their positive feedback.

I mean human, skin contact. It’s an old chestnut of engagement, but it proved itself once again. Even when bits of equipment broke – or were broken before we even started – the audiences really appreciated getting to hold and touch things themselves. This applied as much to the wires, switches and circuit boards of the robots as the cuddly and creepy animals. A ‘robot autopsy’ (bits and bobs from the scrap bin at the Lab) went down a storm in a Bristol primary school and a Pint of Science pub quiz. Watching school students handle a Nao robot as carefully as a baby was a project highlight for me and featured strongly in their positive feedback.

- Keep contact.

I was physically based in the Bristol Robotics Laboratory for the duration of the project, and it made a huge difference being around the researchers outside of our meetings and in between emails. I could get a much better sense of their projects, interests and personalities by seeing them every week, even if I theoretically could have coordinated the project from the SCU offices on the other side of the campus. Being around also helped to give the project a higher profile inside a busy, hard-working research lab where time for public engagement is limited.

- Have contacts.

The project evolved from its main focus of classes at Bristol Zoo Gardens to include a short film with a local science centre, talks and stalls at public events and even a teacher training seminar. Being able to say ‘yes’ to opportunities as they arose from different quarters is a luxury that not all projects can afford, but I found it was important to stay open to opportunities as the project developed. Attention to how the project outputs are worded in the first place helps, so does listening carefully to the needs of participants and interested parties and having a great project manager (thanks Laura Fogg Rogers!).

So how did all of that help with an irascible snake, excitable kids and nervous researchers? Firstly, Zoo staff quickly went to find a snake that would be more amenable to being stroked, to allow for first contact. I attended the session alongside the researchers even though they were leading it. This meant I could give feedback and support, and had the honour of watching as they became more skilled and relaxed. Having seen how they kept their nerve with the uncivil serpent, I knew I could rely on those researchers to handle other difficult situations – like appearing in front of a camera when the opportunity arose. Finally, when we had the chance to showcase their research at another event, we made use of our contacts and took the docile cockroaches with us rather than Indigo the snake.

Corra Boushel is a project coordinator in the Science Communication Unit. Robots vs Animals was supported by the Royal Academy of Engineering Ingenious Awards. Thanks to the Science Communication Unit and Bristol Robotics Laboratory at the University of the West of England and Bristol Zoo Gardens.

No snakes were harmed during this project.