Blog Archives

Behind the scenes at Bristol Museum

Text by Andy Ridgway, Senior Lecturer in Science Communication, images by Marta Palau Franco, euRathlon project manager.

“Artists love this kind of thing,” says Bonnie Griffin, Natural History Curator at Bristol Museum & Art Gallery. The thing in question is a scrawny-looking taxidermy pigeon that’s a victim of moth strike. The moths have stripped away the ‘feathery bits’ of its feathers, the barb, to reveal the rachis – the pointy bits in the middle.

He – or she – was introduced to students on our Masters and Postgraduate Certificate in Science Communication during our tour of the Museum’s natural history store, somewhere that’s normally off limits to members of the public. The tour was part of a day spent at the Museum to get an insight into the inner workings of a museum with a vast natural history collection.

Natural History Curator Bonnie Griffin shows our MSc students some of the extraordinary taxidermy in the natural history store

The pigeon may be one of the less exotic residents of the store but it illustrates the two principle challenges of having such a huge resource; how to make use of a valuable resource when display space is at such a premium and how to stop the objects themselves being eaten or decaying in some other way.

The store has 650,000 residents – all of them dead – and this represents 90-95 per cent of Bristol Museum’s natural history collection. This means there’s only space for 5-10 per cent of the collection to be on display at any one time. It’s not an uncommon problem (and has prompted some at other institutions to consider drastic action).

But ways are being found for the store’s residents to earn their keep. So while the scrawny pigeon is making its living as an artist’s muse (the shiny tropical beetles are popular too), other residents are the object of scientific study. A humming bird, for instance, is giving us a clearer picture of what dinosaur plumage was like – apparently the way the colour and shine are created is the same as would have been the case in dinosaur feathers.

Mysterious samples make up some of the 650,000 items in the collection

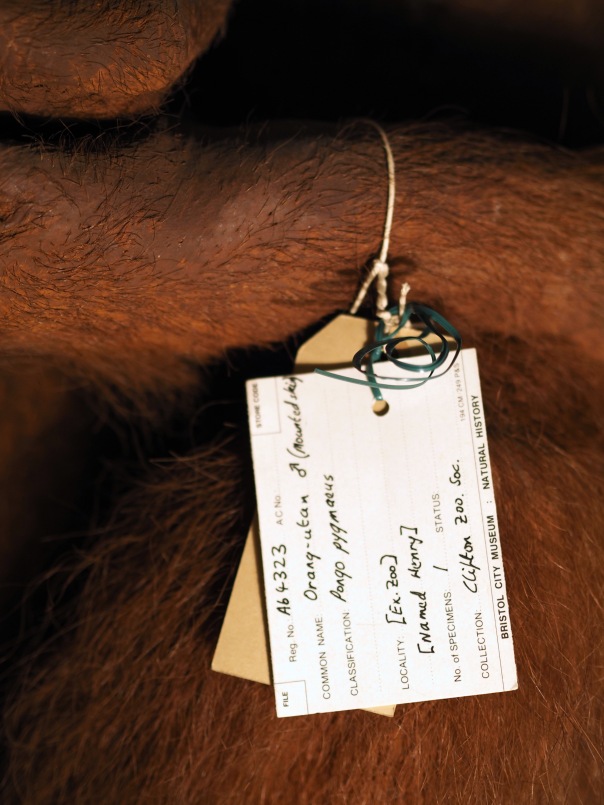

It is Bristol’s history that has led to such a vast collection – its wealthy merchants of past years would pay for specimens from exotic lands to be brought to our shores. And the museum’s proximity to Bristol Zoo is another factor – several of the zoo’s inhabitants have taken up residence in the museum once they have died. Among them is Henry the orangutan, who once shared a cage with his orangutan sweetheart, Ann, at the zoo. Today, the store is taking in fewer new residents and rather than coming from far flung corners of the globe, most of it is roadkill.

Henry the orangutan, formerly a resident of Bristol Zoo.

While moth strike is one of the threats to the natural history collection, pyrite decay (where the sulphite component of the mineral oxidises) is one of the – if not the – biggest threats to the collection in the museum’s geology store. So temperature and humidity down here are continually monitored. In the geology store we were given a guided tour by Senior Natural History Curator Dr Victoria Purewal.

Again it’s the detail known about some of the objects that helps bring them back to life. Take fossil of Pliosaurus carpenteri, that sits on one of the shelves and is the only known example of this species (it’s named after Simon Carpenter, who discovered it at Westbury clay pit in Wiltshire). Thought to be a female, it would have suffered from excruciating toothache in the final years of its life – its fossilised remains revealing signs of a tooth abscess.

Shelves of fossils, some of them unique finds, in the Bristol Museum store.

Thanks to the staff at the museum for such a fascinating insight into their work – it was a valuable day out for our students.